1904, Year of the Prophet

The Vaekirate College of Hjaaris, one of the many small towns surrounding the Holy City of Messara, was hardly distinguishable from the mass of lodgings and workshops and storefronts that surrounded it. People knew where it was because of the hill it sat on, defined by the ruins of Mauris Castle. The old fortress, once commanded by the Tovenaar-Akur* Halei Mauris, harkened to a time when relations between Foedinei and Messara were shaky at best. A time when the Holy City commanded its own professional army of holy warriors, until it was subjugated by Emperor Vokoryn II for the Vaekir's refusal to crown him with the Red Cap.

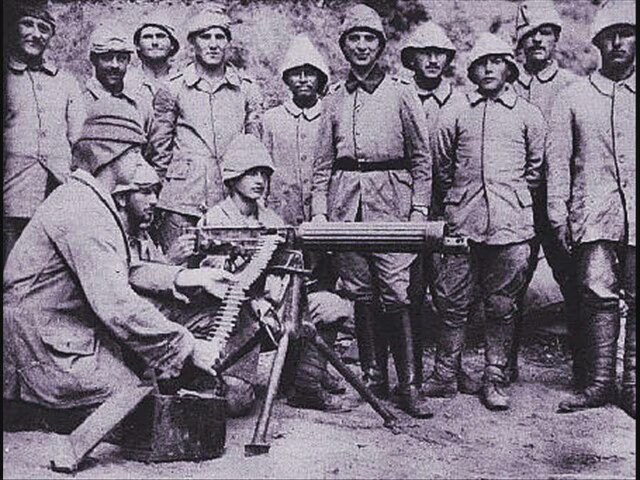

But if there was any resentment against the Empire or any longing for a new Independent Vaekirate, it certainly didn't show here. In fact, the College of Hjaaris had changed very little in the last two-hundred years, no matter the changes and conflicts regarding Vaekirs and Emperors. Its namesake may have been a warrior, but its function had nothing to do with war. Inside the halls of the College, hundreds of peasants and townsfolk from the area trained to become Priests. They sat in lectures on the laws and nature Aed and the Prophet taught by aging Tovenaar in red and white; they studied the Holy Books from dawn until dusk, and sometimes even longer if there was gas enough to keep a few lights running past sunset; and in their passing hours they discussed theology, bringing the grand precepts of their lessons to the everyday issues of their villages and neighborhoods.

The priests-in-training were mostly men but sometimes women, depending on the theological bent of wherever they came from and whoever approved their applications. Regardless, from the moment they donned their white robes, they were equals as far as Aedakom law was concerned. They spoke, argued, and joked in Classical Survaekom, language of the Aedaknam and the Raegarnam,** which they had learned from their earliest days of education in their local Temple Schools. Of course, it was not forbidden to speak common Messaran or Modern Survaekom, but very few would risk seeming incompetent by resorting to this. At least not outside of more private, personal conversations.

Today, a photographer and a journalist from the Imperial Press Service had been welcomed into the College for the afternoon, so they could take pictures and conduct interviews for an ambitious new project:

The Grand Imperial Atlas. More than a simple geography text, this work would detail information on the peoples and cultures of all of Survaek, and perhaps a little beyond too if the reporters could gain access into the Usmyae, Akurr, and the Varian Colonies. The students and their instructors were more than happy to pose and speak for the Press, hoping to spread the word and goodwill of Aed as far and wide as possible.

_

*

Tovenaar is the Aedakom term for a scholar serving the Vaekirate, always trained in theology and sometimes in natural or social sciences. Among them the

Tovenaar-Akur, which no longer exist, were war-clerics of the old Independent Vaekirate.

**The

Aedaknam is the foundational text of Aedak, a specifically Messaran account of the mystical presence and guiding hand of Aed in their ancient history, which was compiled and translated under the reign of the Prophet. It is the source of the Three Principles: Duty, Mastery, and Dignity. The

Raegarnam was written by the Prophet-Emperor himself, and it is primarily a book of law designed to codify the proper application of the Three Principles. Classical Survaekom, an ancient trade language that united the disparate parts of the region that would become Survaek, was not the original language of either work but rather the language decreed by the Prophet for use by the clergy.

_____

Click“Thank you, ladies,” the photographer spoke in Khjaed Dialect. Something to send off to the Imperial Press Service folks for their big atlas. Of course, that wasn't the main reason why the black-robed man was here. Imperial Scribe, 1st-Class Ykakerish Doelae was here for the Bureaucracy, not the Press. And more specifically, he was here for the Census.

“What is your family name?”

“Gyarkerbir,” one of the women, seemingly the eldest, answered. By now the four had broken from their formal poses and scattered a bit in the room, occupying rustic wooden chairs facing the bureaucrat in many directions. It was something of a defensive measure; they weren't hostile to the Bureaucracy or its agents, but they didn't quite trust them either.

“Head of household?”

“Me, Tebrei,” the same woman replied. “I am the oldest sister, we have no husbands or brothers or father alive.”

The Scribe raised his eyebrow. “None at all?”

“We never had any brothers, and our father died in the famine. Our husbands died in the war.” She eyed the visitor quizzically, noticing the slight signs of strain in his expression. “Don't be shocked Mr. Scribe, we aren't the only ones, and we are not the worst-off. The family plot is ours, we can tend to it fine together, we have enough to eat. Some women lost everything to the village council or the magistrate, or to their husbands' greedy fathers.”

“Why so many men lost from this village?” Ykakerish asked, confused at the situation. The question wasn't technically relevant to the census, but the curiosity was too much.

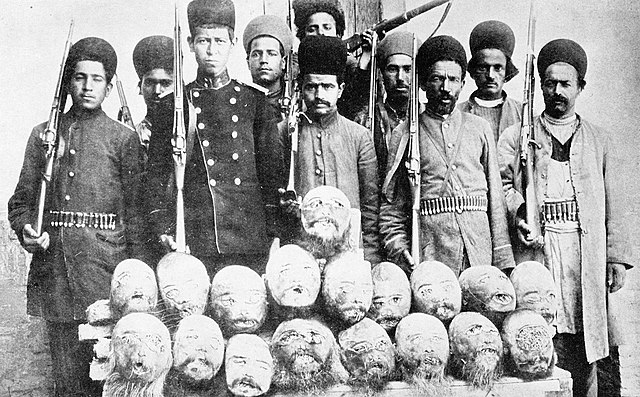

“The Press Service Weekly let us know, the men were all together in a battalion in the First Army, and almost everyone died when they were sent to attack in the Battle of the Long Coast.”

A somber story...but intriguing. The Imperial Press folks would be happy to know their publications were reaching as far as a small village in the Khjaed Province.

“Very well,” he continued. “How big is your plot? And do you own it or rent it? Do you have the deed to the plot?”

“One and one-half hectares,” Tebrei replied matter-of-factly. “We own the plot and our cattle and plows, but we rent the tractor. We got the deed just yesterday, nearly had to beat it out of the magistrate. You're a bureaucrat, see if you can do something about that man.” She transitioned from answering the Scribe's questions to petitioning him seamlessly, as if it were all part of the same sentence. “He uses Reyiriki law which says only men can hold deeds and uses it to rob widows and give plots to his friends. We know this because of our friends Mayeli and Hennei. The elder council looks the other way, even though Khjaedi tradition is against it!”

“I'm sorry, I...” he struggled. “Unfortunately I -”

“You speak Khjaedi well, you are from around here, you understand! Go make the man stop!” She spoke as if she were giving the bureaucrat an order, rather than asking hom for help.

One of the younger sisters spoke up, “Or remove him! Tell your lord to get rid of the tradition-breaker! Or you will have the blood of our friends on your hands!”

Things were escalating quickly. “I will go speak to the magistrate, and I'll let the provincial Secretary know about what's happening.” Scribe Ykakerish Doelae tried to sound as stern and convincing as possible. The Gyarkerbir sisters seemed satisfied enough to stop shouting, and soon the interview was back to its normal course. And they were right, he wasn't even lying, exactly...he would just have to delay their request for some time. His section of the Census task-force had a deadline to meet, after all.

__________

-- Imperial Press Service journalists visit the Vaekirate College in the town of Hjaaris in the Messara region, as part of an ongoing project to make a comprehensive anthropological atlas of the Empire and the surrounding territories.

-- A Scribe of the Imperial Bureaucracy, tasked with completing a small part of the Imperial Census, interviews a peasant family and hears about local injustices.