Ruin fulfils her purpose

Tucked away in one of the many rooms of the divine palace sat Ruina. Hoping to catch up upon what she had missed during her time straying away from the grand stage of Galbar, she made extensive use of the artifact that she had been given. The events that she had missed would forever be lost to her, but now with an unflinching eye she could gaze across the surface of Galbar unimpeded. Though she could not hear words she could at least witness events as they transpired. Of particular interest right now was the events transpiring around Iqelis. She recalled their previous encounter with disdain and thus decided to focus her vision upon him and his companion in order to keep an eye on what they might be doing.

Witnessing their discussion with Homura, Ruina pondered the reason why Iqelis chose to shift into the form of a giant insect. More intimidation games? Some things never change. As the group began to depart westward Ruina rose to her feet. Departing the room, she spent a few moments walking and found herself before the great bridge descending to Galbar. But she did not descend yet. Focusing into her artifact once more, Ruina sought out the group once more to continue watching. If Iqelis was indeed attempting to intimidate other gods again, Ruina had plans to confront him. With the enhancements made to her suit she felt confident in her ability to take the upper hand in a confrontation.

Interestingly, she’d be going there for a very different reason…

Indeed, the looming black figure was nowhere to be found in the vicinity of the rest of the trio. There was a clink nearby, not of a blow upon the luminous bridge, which would not have made a sound under the heaviest of treads, but of crystalline talons striking together as they alighted. There, the divine she had observed not long ago stood upon his two feet, arms folding together after having carried him through the tide of moments.

“The Elder One has need of your aptitude again,” he crackled, somewhere between amusement and irritation, “This time, His will has spoken with His own mouth.”

Ruina could sense him the moment he began to materialize. Opening her eyes and turning her focus out of her artifact for a moment, Ruina turned to face Iqelis and affixed upon him a guarded gaze. When he finished, Ruina pondered. Why she had not heard of this from Him directly? Still, if the words spoken were true, Ruina did not wish to disobey.

Blinking to show some form of motion, Ruina nodded. It was clear that she remained guarded from their previous encounter, and even if Iqelis said that the charge came from Him directly, Ruina wasn’t sure if this was some complicated ploy to entrap her somehow. Speaking at last, Ruina addressed the charge she was given. ”Very well. What is the duty that He had charged me with?”

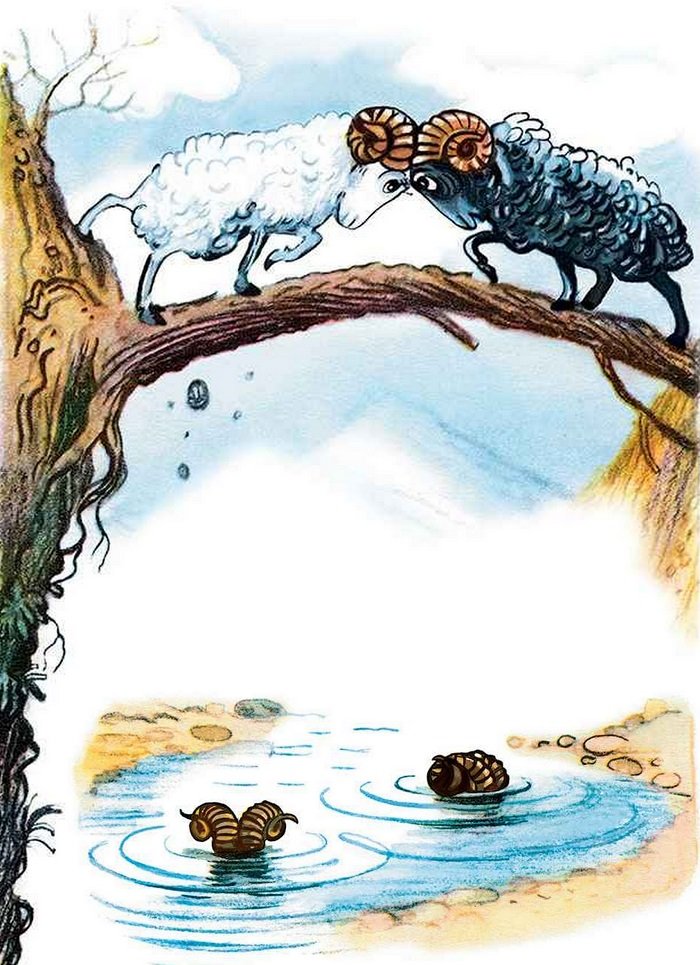

“Down there,” a dark hand pointed at the end of the bridge, where it disappeared into the many-coloured canvas of the Galbar’s surface, “Wait two deathless lives, one I have taken and one I have given. In exchange for the first, I am made to put the second to the test, that He may know it is worthy of His dominion. You, whose art is to forge crucibles, must ensure that mine is not too lax.”

As Iqelis explained, Ruina listened. As she listened, her guarded stance became more justified. Iqelis had taken the life of a god? Then she was right to avoid trusting him. Blinking one more as her gaze shifted from the spot where Iqelis pointed back to him, Ruina spoke once more. ”Very well. Go. I will follow.”

The outstretched arm was joined by another score, and a wave of oily haste pointed the way down the sun-bridge’s golden span.

The Bones were green, mostly, with tough little wisps of grass that peeked out between rocks and whipped in the gusty in-and-out breath of stone-channelled wind. Then they were white, laden with year-round blankets of clean fresh clouds and the snow they left behind, trickling meltwater that fed the valleys and tasted of youth and rock. In between, they were brown. The peaks of Aletheseus’ grave were fertile, but they were also very cold.

Ea Nebel sat on that gravel-studded slope now, between the drab alpine meadow and the lifeless, peaceful summit above. The flank of the dozy Iron Boar sheltered her from the wind, but her knees were still tucked to her chest and her arms around them, a hood thrown over her head. Nothing changed until she yelled.

“Why me? Why am I forbidden?”

Her shout was answered with silence from the Goddess of Honor who listened from afar. The red deity had kept a distance, merely observing Ea Nebel, but never speaking to her. Homura did not hide her presence, as she stood atop a large ledge that protruded near the mountain’s peak. She still held Daybringer, the golden spear shining brightly like the light of the sun as it rose above the horizon.

Only the wind saw fit to speak, and didn’t have much to say.

Ea Nebel abruptly stood, tall and steady. She whirled her finger once, and a black sling tied itself around it, and a stone. She whipped it around and released with a crack of leather at the easy target.

The projectile shot through the cold air and struck Homura, the rock biting deep into the flesh of her stomach. The goddess stumbled back, before the stone fell from her bleeding wound, and she returned to her previous stance, ignoring her injury while she continued to watch Ea Nebel. Their gaze met again, Nebel covering her mouth with her fingertips, eyes wide. Her mouth formed some mumbled word that the wind blew away.

She sat down as quickly as she’d stood. Her arms tightened around her knees, and no more words were spoken.

A rain of loosened pebbles rolled down the slope as the parting outburst of the Flow, whose misty blackness mingled with the waning light of the already distant bridge, eroded the ground under them. In the retreating halo of gold and black, a new silhouette was left standing in the stirring stones.

“The second judge will be here soon,” Iqelis announced flatly, “We can-”

His words broke away into silence as his sweeping eye clambered up the mountain and stopped on the oozing blemish on Homura’s person. It shone in a blinding white flare, and the very next moment he was scrambling up to the edge of the cliff with unnatural vigour, many-limbed like some horrible spider. Dozens of hands gropingly reached up to the wound, and the raucous churning of a buried whirlpool rose from somewhere deep in the god’s frame. A blink, and already his claws were gripping the ledge, the hungry glow of his gaze not far behind.

Ruina did not immediately follow. Instead she turned her focus once more into the artifact she had. Sending her gaze doward to the spot that had been indicated, the first thing she saw was a lightly wounded Homura, and Iqelis racing towards her. To say that her suspicions felt reassured was an understatement. Ruina’s eyes snapped open, and she lunged down the bridge at top speed.

Were it not for the divine material that the palace was hewn from, Ruina would’ve left scrapes and footprints in her wake. Upon Galbar a streaking form rocketed down from the sky to land in front of Homura, and from the cloud of dust rose Ruina. Raising her left arm Ruina seemed to grip at nothing, but the moment before her hand would have closed to a fist, a large blade of bone erupted from her arm.

Unlike what one would imagine, Ruina didn’t flinch at this development. Instead she held it aloft seemingly effortlessly, pointing the tip of the long blade straight at Iqelis’ chest. Her tail joined in this weaponizing, with a large stinger growing from the tip as it raised above her head, much like a true scorpion’s tail. With a firm voice, Ruina issued a stout command. ”Cease your bloodlust!” The god let himself drop back to the lower slope with a discontented growl, his frenzied light fading.

With her command issued, Ruina’s attention turned slightly, to Homura. A soft whisper found its way to Homura’s ear. ”Are you well? What has happened? Is this a trap to slay us?”

Ruina’s gaze remained fixed upon Iqelis’ form, waiting to see what madness would come.

“That is distracting,” the One-Eye remonstrated from below, with an irritated jab of a finger in the red goddess' direction.

Homura had remained still the entire time, her crimson eyes colder than the frigid air around them, but she spoke calmly in a monotonous voice. “I am well, but our brother seems mentally ill. I doubt this is a trap, for it would be a poorly designed one, nor have I detected any attempt to deceive me from either of them. I am Homura, and you have my gratitude for your intervention, sister. Let us allow them to provide a proper explanation now that we are all gathered here.”

With the explanation given, Ruina nodded slightly. The whispered voice returned briefly to Homura’s ear. ”Very well. I will hear them out. I am Ruina, sister.” What would now be notable, with things having grown slightly calmer, is that the weapons that Ruina’s suit had grown were flush with destructive energy. It wouldn’t take much of an examination to realise that they were exceptionally capable of bringing harm to even divine forms. Why would Ruina have such a thing? A curious question to be sure, but interestingly the primary answer to that question had a blade levelled down at him for the moment.

A gentle grey hand alighted on Ruina’s wrist. She looked and saw Ea Nebel, standing with them at last, her eyes exploring every corner of her, down the edge of the blade and up the twisted surface of her armour, around the lethal loop of her tail and resting, finally, on her face. Fragments of thought broke off from the jade rune-ring on her hand and crawled up Ruina’s arm as glyphs. The only sign that she had been swept up in the wave of tension was the doom-claw, resting loosely in her hand, hanging from her index finger with its ring of ivory.

“You’re wearing a corpse.” She did not introduce herself further.

As she felt the hand of Ea Nebel touch her wrist, Ruina’s head and tail snapped instantly to glare at the surprise arrival, but instead of launching an attack Ruina merely blinked as she considered the statement provided. By all accounts the observation was correct, but there was more nuance to it than just being a corpse.

As the thought-glyphs began to crawl up her arm Ruina pulled it free from Ea Nebel’s grip. Releasing the handle of bone that protruded from the blade caused it to retract back into Ruina’s form nearly instantly. As it did, the raw destructive energy that was wafting from it vanished promptly. The stinger in Ruina’s tail followed shortly afterwards, and her tail would fall into being merely a balancing tool once more. Now, at last, she would address the observation. ”It is more than that.”

Folding her arms, Ruina would look back to Iqelis before speaking once more. ”Explain yourself. Why is it that Homura is wounded, with you so eager to finish what was started?”

“That’s-” Ea Nebel interrupted, caught herself, frowned, and continued anyway. “That’s not important right now. Divine Ruina,” she began instead, flicking her wrist to shake off the leaking glyphs, matching gaze briefly with Homura. “I am Ea Nebel, a god for the grave. The one to be put to test. You,” she repeated, slowly, impassively, “you are a grave. Her bones are your blades now. A monument to her hunger. There’s nothing like you in this world.”

Four gunmetal eyes searched Ruina’s own pale jade gaze, tracing the crooked lines of her scars, her bleached white hair, flicking in the same breeze as Ea Nebel’s own. They settled again on Ruina’s narrow pupils, searching for nothing in particular.

Ruina’s eyes narrowed slightly. Not important? A wounded divine being about to be eaten alive by a divine that had previously gone and murdered another wasn’t important? Ruina disagreed quite severely. ”I am told that these trials are happening because a god has died at Iqelis’ hand, and I myself have some unfavourable history with Iqelis. A wounded god with Iqelis charging at them is something that I do consider quite important, given the context.”

“...”

Taking a moment to brush away the errant thoughts herself, Ruina’s eyes hardened to a glare as Ea Nebel began to compare her to a grave and call her unique. Blinking away the glare, Ruina would fold her arms firmly once more before speaking. ”My sister was a murderer from birth. It was by the whimsy of luck that she did not succeed. I took back what was rightfully mine… And it was not a pleasant happening. On this I will say no more.”

“I know,” whispered the gravekeeper. “You don’t need to. Ruina.”

Now Ruina affixed her gaze upon Iqelis, waiting for a proper answer. The whispers coming from Ea Nebel were noted, but for right now Ruina had higher priorities to tend to, so they would need to wait.

“Unlike some, who while away the cycle in keeps and palaces,” the acidic crack of ice shattering over a toxic waste-pit answered her stare from the head of the slope, “I feel the pull of my duty keenly through every drop of the Flow. The spilled blood of an immortal calls to me, compels me to sever the frayed thread, which brings me joy immeasurable. If the Lance-Flame cannot cross a mountain without gashing herself open, she should travel underhill.”

Ruina’s eyes narrowed once more as Iqelis explained himself. The explanation sounded more akin to an excuse, and the barb tossed alongside it made it seem as if Iqelis was doing his best to lessen the blow to himself. Ruina, naturally, wouldn’t tolerate that in the slightest. ”So your given excuse is that you admit you have no control over yourself? Forget not that I am destruction incarnate, and yet show an immense amount of restraint when it comes to my actions. Perhaps you would be wise to begin emulating my choices rather than disparaging them. Regardless, bickering with you is not why I was brought here. Return to the proper course of things, or I shall see to it that your efforts are marked as failures before they even begin.”

At this point Ruina began to tap her claws against her arm, producing three quick tapping sounds followed by a slightly delayed fourth sound as the sharp claws harmlessly impacted on the firm shell of Ruina’s suit. Ea Nebel continued to weigh her with impenetrable eyes.

“Restraint is a fine word for those who would make of sloth a virtue,” jibed the Fly as he moved to a high rocky pass nearby in long leaps from boulder to boulder, “Nor did your Lord call for an envenomed judge. Hark now! Four trials were demanded, and four there shall be. I will test my child for the essential virtues that are required of true divinity to fulfill its purpose. The first ordeal waits in the vale beyond this gulch. Make yourselves ready.”

The demigoddess looked down, exhaled, held it. When she looked up again, it was to stare down the path of the meadow and into the jagged dark of the valley beyond, leaving the bitter tension behind her like a bowstring strung between eyes.

“May the Imperial Sun lead not my step astray,” she prayed. “I’ll see you soon, Father.”

She curtsied once each to her judges and leapt down from the ledge, coattails fluttering like windblown fire as she descended. Her silhouette soon grew small and lonely on the meadow. Ea Nebel summoned the Monarch’s talisman back around her neck under her hood. She knew not what lay before her: what terrors of the mind, what agonies of the flesh, what temptations and humiliations of the heart. So she was grateful, if nothing else, for its warmth.

The Iron Boar grunted a sad and knowing farewell, and she stopped, once, to force a smile in its direction. Then she turned around no more, and disappeared into the valley.