Nation Name:

The Varsovian Crown (Ussuri-Varsovian Commonwealth)

Banner:

Basic Population and Demographics:

84 systems – 700 billion inhabitants

Shravians: 20%

Ayar: 35%

Humans: 42%

Other: 3%

System of Government:

BUREAUCRATIC MONARCHY

The current monarch is Kasimir: Head of House Preslid, Bearer of the Varsovian Crown, and Co-King of the Ussuri-Varsovian Commonwealth

In Varsovia there is one King, one royal family, and fourteen billion nobles. That is to say, every Shravian is considered a noble. In return for royally-guaranteed hereditary estates and pensions, nobles owe both taxes and service to the Crown. This service may be military, but more often it is in the enormous Royal Bureaucracy. Nobles must also implement a variety of projects decreed by the Crown, such as infrastructure, though in practice this is managed in a centralized manner by the Bureaucracy rather than fiefdom-by-fiefdom. Refusal to fulfill noble duties is punishable by confiscation of properties and imprisonment, but such acts are few and far between. Everyone knows that for all the talk of noble privileges, true power lies in the Crown.

Although every noble family technically has an estate, this is almost always a stake in a larger, concentrated operation. Non-Shravian serfs attached to factories, mega-farms, space stations, etc. are technically subjects of nobles and therefore only indirect subjects of the Crown, but there is almost never a single noble family they owe loyalty to. Nobles could theoretically pool their resources to raise their own political infrastructure, but de facto there is no bureaucracy outside of the Royal Bureaucracy. In this way, the serf class as a whole is effectively controlled by the nobility as a whole, but this authority is administered primarily through the Bureaucracy under the King. Exceptions, where a single noble family or a “board” of noble families directly rules serf communities and institutes its own laws within the fiefdom, are extremely rare and kept under very close watch. The Crown also has its own demesne, but in practice the only distinction between this and most other noble territories is that the whole profit of all operations goes directly to the Crown.

Outside of noble holdings, which make up about 90% of the Varsovian economy and account for 75% of its population as either nobles or serfs or slaves, there are peasant holdings. They have a more “hands off” relationship to the Bureaucracy, as they have freedom of movement and autonomous local assemblies. Also, unlike serfs, peasants may own property – including weapons and even slaves. Their only duty to the state is taxation; though military service by peasants is fairly common because of the salaries they can earn, it is entirely voluntary from a legal perspective. Thus, ironically, peasants are in some ways freer than nobles, though they lack the same guarantees to permanent hereditary estates or lifelong pensions. Peasants are also barred from high-level political and military positions, though they can have political power within their own local administrations. Therefore, peasants have no representation within the larger national institutions of power.

Important People:

King Kasimir Preslid

Head of House Preslid, Bearer of the Varsovian Crown, Co-King of the Commonwealth. Kasimir is a fantastic administrator, politician, financier, and innovator: the pride of the Preslid line. Ve is the product of the union of Preslid with a minor but strategically-placed family of noble industrialists whose name history has already forgotten. At the time of vis spore-fusion, little was expected of the child-to-be beyond a useful alliance and perhaps a minor administrative role. But, to the chagrin of those far higher in the traditional line of succession, Kasimir simply demolished the competition in every test of merit that mattered to the banking family. The former House Head, Vladisvla Preslid, initially hesitated to officially designate ver as heir for fear of provoking an assassination. However, by the time of Vladisvla's death, Kasimir had built unbreakable respect and authority in the family for vis decisive role in mobilizing the war economy and orchestrating the Ussuri-Varsovian alliance that won the Preslids their dominance of the core systems. At that point, passing on the Crown was a mere formality.

Admiral Izydor Jagelon

Hailing from an one of the oldest surviving Shravian dynasties, Izydor Jagelon was an opponent of the Varsovian Crown's ambitions...until ve saw the writing on the wall and defected. One of the first turncoats in the fleets of those who stood against House Preslid's expansion, Admiral Izydor skyrocketed through the ranks of the Varsovian Royal Navy. But as successful as ve became, it is said that something broke deep inside ver when ve submitted to King Kasimir. Ever since the unification of Varsovia, Admiral Izydor Jagelon has been known for vis unusual proclivity for machines, and particularly integrating verself with them. The elderly archduke is now more machine than Shravian, retaining only vis brain, essential organs, and fragments of vis face in a disturbingly asymmetric -but effective- mechanical patchwork.

Dominant Species:

SHRAVIANS

Shravians are a species that defies easy categorization, seemingly both animal and fungal in their characteristics. In their adult form, they appear as bipedal amphibians standing about one meter high. However, their natural reproduction is exclusively asexual: about six times per year Shravians “spit out” spores that look nothing like their future forms. The spore form, externally, appears as a moldy ball that slowly “morphs” into an adult over the course of 4-7 years. It is generally accepted that Shravians do not achieve sentience until about the age of 2, lacking a brain entirely when “born.” Internally, of course, both forms -as well as the intermediate stages between them- are both animal and fungal. Their individual cell structure is fungal, containing both chitin and glucan, and like fungi they decompose and feed on organic matter through their skin, lacking any devoted digestive system. However, adults do have lungs, skeletons, internal zygote (spore) generating organs (connected to their mouths), and a generally animalian form. Even spores have rudimentary hearts and circulatory systems.

A major complicating factor in accounting for Shravian biology is their near-millenium of artificial genetic modification. This has resulted in staggering genetic diversity that the species' natural reproduction would not normally produce. Embedded in this difference is a hierarchy between those with access to the most comprehensive genetic “improvements,” granting lifespans of centuries and due to various advantages, and those with lesser access who generally live to about one-hundred. Most, but not all Shravians possess facial characteristics reminiscent of humanoids, and there is speculation that one of the earliest technologically-imposed genetic modifications to the long-spacefaring species were modeled after certain advantageous humanoid characteristics. Almost all Shravians would deny such a claim, however.

Indeed, unmodified Shravians disappeared so long ago that even records of their original biology have been lost to time – or perhaps destroyed at some point after their extinction. It is generally thought that these “lesser Shravians” lived no longer than twenty years, lacked eyesight entirely, and had no mouths - simply accumulating hundreds of dormant spores inside their bodies that burst out after death.

Compared to the average human, the average Shravian is much smaller and slightly weaker, but stronger relative to its size. Shravians have a number of redundancies that make them significantly more durable than humans, such as 2-3 hearts and an entire network of small lungs under thick layers of skin. Related to the latter is Shravians' ability to open “respiratory pores” in their skin; they can also breathe through their mouths, but this was almost certainly an early genetic modification for the purpose of vocal communication. The average Shravian is slower running but faster swimming than the average human. It has roughly equal visual perceptiveness to the human, but much more refined senses of touch and sound. Most Shravians cannot smell, and those that can usually do so through the assistance of cybernetics in addition to genetic modifications. They are capable of feeding on practically any organic matter, allowing a very wide range of possible food to consume, but they also require about double the sheer caloric intake of a human. Furthermore, if a Shravian is unfortunate enough to go without food for around three weeks, the body will begin to eat itself from the outside in. Their more “fungal” parts, most notably their skin, can regenerate over hours what would take humans days, but their more “animal” parts heal only about 1.5 times the human rate.

Minority Species:

-- AYAR

Ayar are the quasi-humanoid talpids native to Antoviya. They have markedly cylindrical bodies covered in dark fur, unusual strength for their size (standing no more than a little over 5 feet tall), thick hands bearing clawlike nails and two thumbs, an acute sense of smell and hearing, black bulbs of eyes suited to low-light vision, and a high tolerance for carbon dioxide. Hence, Ayar are natural burrowers. However, they have better daylight vision, a less-developed sense of touch, shorter snouts, and larger arms and legs than their evolutionary ancestors, allowing them to live comfortably both above and below ground.

Ayar are difficult for many foreigners to distinguish among by sight; they identify one another primarily by smell. However, the talpids make extensive use of all five basic “senses” and can communicate with spoken and written language, like most other species.

-- HUMANS (SURVAEKOM, SAFAVID)

Survaekom and Safavid are the same species as Terran humans, although even to this day they still distinguish themselves due to ancient cultural differences. The former two began as very distant colonies from Earth, developing into entirely independent polities so far-off and distinct that would not even participate in the crisis of the Democratic Confederation, Solar Federation, and Imperium. Nonetheless, there are no biological differences worth noting among the human groups. There are also Terrans in Varsovian space, legacy of botched Imperium attempts at establishing direct rule in the region, but in such small numbers that they are practically microscopic within the Kingdom's general population.

Culture:

Class Structure

The nobility, encompassing all Shravians (20% of the population), constitutes both an “upper” and a “middle” class of Varsovia. At the very highest level there is, of course, the royal family itself, while at the lowest there are lesser aristocrats with bankrupt estates forced to live off their pensions alone. Yet, all nobles are owners of productive forces. Pensions are low enough that they have “incentive” to compete with each other to develop their estates' capacities, but even a bankrupt noble cannot loser vis property entirely. Thus, nobles can get away with some level of “complacency,” and they have room to prioritize goals other than sheer profit, such as stability. Of course, individually nobles do not really manage economic or social affairs; instead they do so collectively through the Bureaucracy, except for the odd “great noble” who owns an entire district of vis own. De facto, therefore, the vast majority of the nobility is more comparable to a professional class than a bourgeoisie. They work, either as military personnel or administrators, to earn their representation and influence in Varsovia's social organization. They have little to gain from rebellion, and are the most stable and loyal class of Varsovia.

The free peasantry forms a layer not far below the nobility in many respects. Peasants constitute about 25% of the Varsovian population. They too own means of production, either as cooperatives/communes or invididual smallholders. Yet, their economic power is disproportionately low compared to their population, as their productive forces they “own” tend to have limited scale. While a group of nobles may own a vast industrial complex spanning many city districts and employing cutting-edge techniques, a free peasant cooperative rarely expands past the equivalent of a single factory. Thus, peasants tend to concentrate in industries where economies of scale are small, especially where one or a few individuals can manage all they need for their operation. They tend to dominate skilled sectors such as computer maintenance, civilian ground vehicle repairs, publishing, and translation services. Those who deal in industry and agriculture work in niches where small operations can produce and sell efficiently. However, there are some exceptions: in a few particularly autonomous peasant-dominated regions, they work in all sectors across diversified economies that are mostly self-contained. Also, in general, peasants can bolster their production by “renting” serfs or buying slaves. These practices, needless to say, create some antagonisms between peasants and their lower-class counterparts. With relatively few duties to the state and a fair degree of autonomy, peasants also tend to enjoy a level of material and social security superior to serfs and unimaginable to slaves. Those who cannot entirely support themselves with their properties can find decent wages as soldiers or local administrators. Therefore, much to the benefit of the Preslid regime, over time peasants have come to side more with the nobility than with their less-privileged fellow nonhumans when it comes to social questions. More strongly than these others, the peasantry has come to identify with Varsovian nationalism over the dead-and-buried Revolutionary Republics or the even more ancient non-Shravian empires of old.

Serfs constitute by far the largest class in Varsovia at about 50% of the population. They are the primary exploited class in their society's economic order. They are “attached” by law to noble estates, confined to districts or towns serving a particular economic operation (or even a particular part of such an operation). On settled planets, these are usually industrial complexes or mega-farms, but can also be mines and even office complexes in some cases. In the “beyond,” serfs may be dock-workers attached to orbital stations, janitorial staff attached to starships, deep space miners attached to asteroid outposts, or any number of other “low skill” workers necessary to run the machinery of interstellar commerce and travel. Everything they maintain and produce belongs to their lord(s), though they get to keep a designated portion, usually but not always in the form of wages. Also, depending on the industry, they tend to have a respectable level of autonomy so long as they meet the production quotas of their superiors. Regardless, the demands of serfdom are heavy, taking both physical and mental tolls that fuel no small social resentment. From the serfdom rise acts of defiance such as strikes, walkouts, riots, and even the occasional armed revolt. These tend to be sporadic when considered from a distance, but sometimes they manage to organize across larger networks. Naturally, these acts are met with the usual Varsovian combination of force and diplomacy, and for now they have not succeeded in altering the status quo. Notably, there do exist a few “privileged” sub-classes of serfs. Chief among these are serfs who work for the military in production, logistics, and basic maintenance. Although the process has been strained, serfs like peasants are gradually adopting Varsovian nationalism – even their rebellious demonstrations often take a nationalist tone and seek to negotiate the terms of serfdom rather than abolish it entirely.

At the bottom of the social ladder are slaves, making up some 5% of the population. About half of these are not hereditary slaves, but rather prisoners from the peasantry or serf class. The other half hold a status that goes back to the beginning of the Shravian Empire. While prisoners might think of themselves as outcasts or delinquents from a social order that they take as a given, hereditary slaves are attached to the system only by chains and gun barrels. Both classes of slaves, of course, are kept under heavy, militarized supervision – usually by peasant Peacekeepers. Unlike in the Ussuri Hetmanate, there are neither “privileged” groups of slaves with special rights nor “lower” slaves regularly worked to death. The only advantage some slaves have are as prisoners from the peasantry, as their families may petition for redress in face of abuses. The rest, both prisoners and hereditary slaves, live grinding lives that could be described as slow deaths. Too valuable to simply work to the breaking point, they “fill the gaps” where nobles find serf labor inadequate or peasants need “extra help.”

Shravian Culture

Varsovian cultural values center on a sense of modernity, progress, and prestige. Varsovian Shravians adopt all manner of genetic modifications that Ussuri would deem completely useless and even absurd, such as cosmetic “enhancements” and boosts for leisurely competitions, such as the infamous race for ever-faster “clicks per second” in holo-game tournaments. Particularly among the bureaucratic nobility, all public life is a “friendly competition.” Varsovian Shravians, both military and bureaucratic, are also known to lean heavily on cybernetics where biological modifications fall short.

As for the Ussuri, Varsovian nobles know no religion. In fact, they tend to look down on the very concept of spirituality as a foolish superstition only suitable for “inferior races.”

**IMPORTANT NOTE: Shravians have no concept of gender, nor have they ever had one. In fact, they find the concept arbitrary and even disgusting. Thus, their pronouns are gender-neutral.

-- A Shravian spore, until it is considered sentient, is simply referred to as “it,” like an inanimate object or a robot.

-- Once considered sentient, a Shravian is referred to as VE (SUBJECT) / VER (OBJECT) / VIS (POSSESSIVE).

Non-Shravian Cultures

A millenium ago, much could have been written about the vibrant cultures of Survaekom, Safavid, Ayar, and Tr'Kan. Now, after countless generations of subjugation, only the barest remnants remain. The most notable of these enduring cultural marks among humanoids is the philosophy of The Mountain, an extended metaphor for life as the careful descent from a misty, unknown peak to a lush base to the eventual return to the ground in death. Related to this is their almost universal tradition of burial, as opposed to the predominant Shravian practice of cremation. Among Ayar, the concept of spirits and the watchful eyes of ancestors remains common to this day, and many continue to possess and produce small religious statues and shrines.

Tr'Kan, who were subjugated later and less completely than other non-Shravians in the old Empire, have retained more of their original customs. In the Ussuri Hetmanate, they could be said to still have an entire living culture continuous with what was before. In Varsovia, in contrast, the relatively small Tr'Kan population is entirely diasporic and lost more of its connection to its roots. They keep their holy books, but they have little sense of the locations they reference or the practices they refer to. They congregate for festivals, but their underlying significance is only vaguely understood if at all. In many cases, old meanings that were lost have been replaced with new ones heavily influenced by Shravian thought. For example, the most common of Tr'Kan festivals, the Sun Festival held every month, is now associated with the “continuing progress” of the Tr'Kan people in Varsovia.

History:

Origins of Modern Shravians

For many millenia, Shravians lived on their homeworld of Kyav as highly egalitarian societies. Although “civilization” and technology were harnessed to impose some stratification, even this was distinguished by entire “strains” and nations rather than families or inheritance – concepts that had no meaning to Shravians at the time. The smallest, most indivisible unit of community was the village – or later the district. And even between these communities, differences were never perceived to be especially large. War was infrequent and class oppression was mild in comparison to the civilizations of most other species – the more pressing issue as population grew over time was disease, which could kill off entire strains of genetically near-identical Shravians all at once.

Shortly after they entered their space age, some 2,500 years ago, Shravians were thrust uneasily onto the interstellar political scene. They quickly recognized the threat of other species, achieving rapid political unification as the Shravian Federation and building up armed forces to match their potential aversaries. More importantly, they looked to ways to shield them from the inevitable tide of foreign microbes, refining the art of genetic modification to allow all manner of engineering spores, and to some extent even adults Shravians. The technology, however, was difficult to make available to their entire population: Those at the greatest risk of unwanted interstellar contacts were prioritized. The modifications primarily reached soldiers, space fleet personnel, interstellar transportation crews, ambassadorial teams, and scientists. The resulting political ramifications were surprisingly deep and lasting.

Shravians whose work dealt with the “outside” were not merely protected from foreign disease. They were equipped with a range of augmentations to aid in travel, communication, and endurance among other traits. As they played the decisive role in connecting Shravians to the greater interstellar community, soon they became the only Shravians capable of doing so. Others lacked not only the skills, but the biology to participate in these new institutions. And as these differences accentuated, Shravians benefiting from genetic technology became less and less willing to share it. “Soft” stratification grew sharper and sharper over time.

But it would take one more step in biotech to bring Shravian society fully into its “modern” form. This was the invention of spore fusion. Two spores could be “grafted” into one. For the first time in Shravian history, the concept of family became meaningful – though only among the elite. And this was enough to truly stratify Shravian society into a multi-layered hierarchy. Wealth and power concentrated in fewer and fewer of these new families, and in turn these families monopolized the best of genetic – and later cybernetic – improvement technology. So powerful did some families become that they eventually formalized their implicit political power, becoming the first nobles.

An Empire is Born

These new authorities staked claims over various lands, settlements, and “lesser” subjects in the Federation. They vied with one another for supremacy, but in the face of powerful alien neighbors they never escalated matters as far as civil war. More out of necessity than preference, they regulated their disputes in the still-extant Courts of the Federation, transformed into arenas of contest and negotiation for the aristocracy. As the Shravians colonized their own system and beyond, they continued to militarize, but not only out of fear. Internal war could not be afforded, but external war could provide avenues for nobles to increase their power.

The first great interstellar war in Shravian history took place some two thousand years ago. The opponent was the Grand Survaek Empire, at the time a great regional power with its fourteen systems. It was ruled by humans known as Survaekom, but also included many billions of reptilian Tr'Kan, four-armed and four-legged sentient lizards over twice the size of a human and possessing many times their strength. The Survaekom had been locked in a cold war with the neighboring rival human Safavid Empire for centuries, and the outbreak of hostilities between them provided the perfect opportunity for the hereto-unassuming Shravian Federation to strike.

No one could have imagined how completely and utterly the Shravians vanquished their foes. With the aid of the Tr'kan, who had no desire to be pawns in the Survaekom-Safavid contest, the Federation swept over the opposition and immediately followed with a conquest of the weakened Safavid. In the space of two decades, twenty-three systems fell under Shravian control.

However, the speed of victory did not mean it came easily. To properly match their enemies' manpower, nobles conscripted hundreds of millions of “lesser” Shravians into military service, providing only rudimentary cybernetic enhancements to prepare their bodies for war. The bloodletting on both sides was immense. And worse yet was what followed.

Exposing hundreds of millions of unmodified Shravians to the great beyond had exactly the consequences the Federation had feared for so long, until recent age in which the lives of normal “citizens” had become disposable to the new elite. A series of plagues unlike any seen before ravaged the genetically-unprepared population in cataclysmic proportions. In just a few short years, an estimated 60% of the Shravian population died off. Naturally, non-Shravian subjects across newly-conquered territory immediately exploited the opportunity, while desperate “lesser” Shravians rose to arms against their rulers as well. The fires of rebellion raged across the Federation.

Records from this period of civil war are scarce and incomplete. All that is known for certain is that a single Shravian noble family, led by a brilliant commander, succeeded against all odds in putting down rebellions across the Federation by around 160 IC. With the uncontested loyalty of the army and navy, this commander named verself Emperor of the Shravians, and proclaimed vis family with no small arrogance as Shravilid.

The Rise and Fall of the Shravian Empire

One of the earliest changes brought about by the new regime was the mass enslavement of all non-Shravians in the Empire. Deeply mistrustful of other species and requiring massive numbers of sentients to replace the mostly-dead Shravian underclass, the imperial authorities placed Survaekom and Safavid under a vast surveillance network as they put them to work in industry and agriculture. Where the slave population occasionally fell short, the Empire acquired more from the notorious slaver empire of Antoviya, a nation of few systems but immense population whose raids seemed to reach every corner of the quadrant. The dominant species of Antoviya, the tunneling talpid Ayar, had long fed parasitically off of Survaek and Safavid for their own slave labor purposes.

Ironically, this same empire would be the Shravians' next target of conquest. Antoviya saw its own period of mass rebellion, and their nobles would fail to put it down. The radical syndicalist Revolutionary Workers' Union was declared, uniting Ayar and former slaves in a grand quest to end all systems of domination. The Shravian Empire could not tolerate such a state to exist in its vicinity, and over a brutal century-long campaign the systems were re-enslaved, this time the Ayar themselves as well as their alien comrades. The Ayar home planet was rendered unlivable by repeated nuclear bombardments, except deep underground where independent remnants exist to this day.

Notably, in this war, the Shravians' Tr'Kan allies not only refused to join but, fearing the Empire's expansion, funneled arms and supplies to the RWU. They too were subjugated by an increasingly mechanized Shravian war machine, though they would plague the Empire with intermittent rebellions for centuries to come.

From there, for many centuries the Shravian Empire's expansion met little opposition. Systems were either colonized or, if inhabited, conquered in mere months. At its height, the Shravian Empire held over two-hundred systems under direct rule, and it received tribute from a great many more along its borders. The only real wall to further conquest came with the Terran Empire. However, sharing certain values and uneager to risk their internal stability with such a gargantuan war, neither side was inclined to fight the other for territory. Aside from a few border skirmishes, the two Empires maintained a stable if uneasy peace.

So things stayed for nearly a millenium, until about six-hundred years ago. Then, however, came the Time of Troubles. Periodic rebellions among the slaves and plagues which regularly decimated the lowest rungs of Shravians were not new to the Empire, of course. Yet, eventually they hit with such intensity and scale that a crisis emerged. A disease which seemed to ignore most Shravian counter-measures, even among the lower nobility, spread across the entire Empire. Ambitious aristocrats who sought greater power and autonomy in the Empire rose in open defiance of the Shravilids. Species of all kinds rose in a great, coordinated rebellion under the banner of a revived RWU. And on top of it all, the Imperium finally made its move against Shravian border worlds.

Imperial authority crumbled. On the Border, military commanders took drastic measures to quarantine the sick and contain rebellion, eventually cutting contact with the core worlds altogether. In the Core, Shravians died in droves while revolutionaries and noble rebels took control of larger and larger territories. In the midst of the chaos, the Shravilid Dynasty was massacred to the last individual.

Then, of course, came the Terran Empire. Taking advantage of the immense instability, it swept in and planted its flag in every corner of Shravian space. Although the humans failed to maintain direct control in the highly chaotic region, opting instead to exact regular tributes from Shravian petty lords, they put the final nail in any hope of re-stabilization. It was more than a disaster. It was the end of the Shravian Empire.

The Core Worlds: Fragmentation and Re-Unification under Varsovia

While the civil war on the Frontier was a contest of might, in the Core negotiation was key, at least at first. Nobles seeking to preserve or re-assert authority over former slave populations were forced to either make concessions or lose it all. Piecemeal, fiefdom by fiefdom, slavery was all but abolished in the core systems as the vast majority of non-Shravians attained new status as “free subjects.”

Chief among the reformist polities was the Duchy of Varsov, uniting the metropolitan planet of the same name as well as the key garden world of Rugaz. Its ruling family, the Preslids, developed by far the most comprehensive social framework in the Core for integrating non-Shravians into their domain. Somewhat controversially, they promoted all surviving Shravians into the nobility, a move that allowed them to cut away at the power of more powerful vassals while creating vast ranks of loyal followers. Non-Shravians were classified as free peasants, serfs, and (a small minority of) slaves. Where exactly a community landed on this spectrum was more or less a function of how costly subjugating them would be. The better-organized and better-armed secured status as free peasants owning their own means of production, forming a stratum of relatively well-off small producers and independent laborers. In contrast, their weaker counterparts were forced to settle for status as serfs tied to noble-owned industrial blocks, mega-farms, and mining complexes among other economic facilities. Those who stayed slaves were the unfortunate few who had never succeeded in arming or organizing themselves in the first place, or who were targeted for forceful subjugation as an example to “encourage” others to negotiate.

Needless to say, the process of building this social order was not entirely smooth. A combination of force, espionage, and skillful diplomacy were required to bring non-Shravians to accept the new social contract. Reactionary Shravians enraged by Preslid reformism had to be placated, subjugated, or simply eliminated depending on the situation. Over time, however, the changes consolidated into a stable regime.

Yet, the Core remained politically fractured. Varsov was merely one of the more powerful among dozens of other small monarchies as well as revolutionary holdouts. And although the Terran Empire had stopped trying to create provinces in Shravian space, its tribute collectors had been known to send fleets against anything smacking of Shravian consolidation. The money would only keep flowing, they figured, if they kept the Shravians weak and divided. If anything, the few Shravians who even expected re-unification were looking to Shravian homeworld of Kyav. Even the Preslids themselves were not entirely aware of their advantages: Much of the old Empire's population and industry had left Kyav and re-concentrated in Varsov, but the geopolitical shift was gradual enough and available information so incomplete that it had gone virtually unnoticed.

This hidden advantage only became apparent when Varsov was attacked by ambitious neighbor lords 258 years ago. The Preslids mobilized their fleet expecting a desperate fight against superior numbers, but the actual battles proved the opposite. The Ducal Fleet not only outnumbered, but out-gunned its opponents by a wide margin. The war of defense quickly became a war of conquest for the Preslids. Terrified of the social upheaval they would face if war hit their planets on the ground, Varsov's enemies were soon offering their surrender and vassalage. Instead of agreeing, however, the Duchy opted to secure the defections of their opponents' underlings. Much like their strategy at home, the Preslids bought the loyalty of the lower nobility and disinherited the high.

In a few short years, the war was over. Vladisvla Preslid was now ruler of some nineteen systems, and the crumbling Terran Empire was no longer capable of containing him. To celebrate the victory and the birth of a new empire, ve established the Varsovian Crown. It was not only a title, but a physical crown commissioned by the new King. It was of unprecedented strangeness, a headpiece that seemed to extend into innummerable translucent “towers” with soft glows emanating from ever-changing parts of the crown. Like a small model of the Capitol Palace in Varsov, yet so visually complex that it was nigh impossible to fully distinguish as a particular set of shapes. A crown finer and more wondrous than that of the Shravilids, a clear message to the other lords of the Core Worlds.

For a time, Varsovia's neighbor noble states began to unite in confederations to contain the rising power. They too, after all, no longer had to fear Terran tribute fleets. Unfortunately for them, the Preslids continued to show a knack for attracting defectors. Unevenly but surely, Varsov continued to annex territory through its usual combination of carrots, sticks, cloaks, and daggers. About thirty years ago, effectively all Shravians of the Core were subjects to the Varsovian Crown.

The only remaining opposition to Varsovia's dominance were the Revolutionary Republics, expansive rebel holdouts encompassing large territories, varying from continent-sized states on nominally Varsovian planets to entire independent systems. Against these enemies, diplomacy and espionage were much less reliable. Brutal, grinding ground campaigns simply could not be avoided. Varsovia was able to score a series of initial victories using elite troops supported by space fleets, but they couldn't make it farther than beachheads and a few major urban centers. Simply lacking the numbers of Shravians to effectively take and occupy such large territory, King Vladisvla tried sending in peasant and serf troops, but this only seemed to strengthen the rebels as droves refused to fight and some even joined them via desertion and mutiny. Worse yet, as powerful as Varsovia's industry was, it lacked the raw resources to meet the protracted campaign's logistical demands.

Vladisvla died before ve could see the final restoration of the Core Worlds under Shravian suzerainty. This task would fall to vis heir, Kasimir, who assumed the throne a century ago. A brilliant administrator and farsighted diplomat, Kasimir made a move few expected: Ve made contact with the Border. There, Kasimir found the perfect opportunity in the Ussuri Hetmanate, in many ways Varsovian Crown's counterpart in the region. Where Varsovia had a vast navy and industry but required troops and raw materials, Ussuri had a huge Shravian population and expansive mining networks but required ships and advanced manufacturing. Hetman Ivan Sirakov and King Kasimir Preslid each had exactly what the other needed.

An alliance of opportunity emerged, and slowly but surely each side achieved its dream of total dominance in its region of the former Shravian Empire, a process that took about ninety years. Yet, through this each also became dependent on the other. Whatever their ambitions, the two monarchs could not simply turn on each other without risking the breakdown of their own nations. It was agreed that neither would be Shravian Emperor. But someone would be: Two years ago, spores were fused to create an heir to both the Crown and the Hetmanate. The Ussuri-Varsovian Commonwealth was declared.

Varsovia, of course, continues to act more as an allied nation to Ussuri than a fellow component part of a single empire. Indeed, two centuries of separation created a vast social and cultural gulf between the two. Varsovian Shravians see their Ussuri counterparts as useful warriors due respect for their role, but certainly not as equals. Many do not even consider the Ussuri civilized, with their outdated slave society and their denial of universal nobility for all Shravians. Can even a legitimate heir unite such different people as a single Shravian Empire? Will the Commonwealth union even last until the unnamed heir can assume its throne?

Military:

OVERALL SIZE: 18 billion total military personnel

-- 20 billion Peacekeeper reservists

-- 10 billion active Peacekeepers

-- 7 billion Varsovian Royal Navy personnel

-- 800 million Special Operations Police

**In a state of emergency, an estimated 30 billion serf conscripts can be mobilized within 3 months.

TECHNOLOGY

Terrestrial Forces

-- Infantry Armor: Yeomen Peacekeepers wear ceramic armor with integrated sensors and digital interfaces, fairly old but reliable designs. Only nobles have access to power armor. This is divisible into two groups. The first is the battle-suit, a heavy mechanized frame that is more of a vehicle than armor in the traditional sense, used by all Shravian Peacekeeper officers and by the Drop Patrol. The second is “true” power armor, worn like “normal” armor but powered to increase strength and speed. This particularly expensive armor is available only to VSOP, and is integrated with personal shielding and experimental stealth fields.

-- Shielding: Battle-suits are large enough to integrate electromagnetic shielding without too much effort, though the strength of the shield predictably varies in proportion to the size of the suit. Sky Patrol aircraft also use electromagnetic shielding, but Yeoman Peacekeeper vehicles are generally not considered to be worth the expense. Recent advances in miniaturization also allow for personal shielding, but at present only VSOP has access to this extremely expensive technology.

-- Vehicles: The bulk of Peacekeeper Vehicles are thruster-powered aircraft in the skies and armored hovercraft skimming along the ground. The former can use a combination of adjustable multi-facing thrusters to achieve all manner of mid-air maneuvers. Also notable are the battle-suits, whose larger variants are more like walking tanks than “infantry.”

-- Projectile Weapons: As relatively cheap but durable weapons, light gas guns are the mainstray of the Yeomen Peacekeepers. They have power near that of magnetic accelerators, but without the cost in energy and materials. But, the need for cartridges makes their ammunition capacity noticeably lower. In preparation against the potential for well-armed rebels, the Yeomen also have access to a range of missiles, often attached to small tanks or aircraft, but also including many should-mounted variants. Missiles are also a common weapon in the Sky and Drop Patrols, where Varsovian advances in miniaturization are more apparent. Hundreds, sometimes even thousands of small-but-powerful guided missiles can be stored in a single gunship or large battlesuit. In order to counter electromagnetic shielding, ceramic “shield buster” rockets are also common.

-- Plasma Weapons: As a species with a number of biological redundancies, Shravians know well how hard it can be to kill someone with a bullet or even shrapnel. Thus, although they still employ light gas guns as rapid-fire weapons and artillery, the favorite weapon of noble soldiers is the plasma beam cannon: a particle accelerator firing plasma at near light speed. The combination of extreme heat and kinetic energy is enough to obliterate anything biological beyond any hope of recovery. The drawback is that such energy-intensive weapons cannot manage “automatic” fire without overheating or exploding. They also require battery changes about every 20 shots, depending on the model. Most plasma cannons are fairly bulky, requiring the strength and size of a battle-suit for an individual to use, but as with many things VSOP has access to a special line of miniaturized small-arm variants. Varsovia also deploys plasma throwers, which simply spew plasma in an expanding stream. These lack the range and punch of plasma beams, but they are far cheaper to produce and remain devastating at close range.

Space Forces

-- Armor: For any vessel cruiser class and above, Varsovian Royal Navy armor comes in two layers. The first is ceramic, designed to absorb heat and kinetic impact. When a plate cracks, it ironically becomes more resistant to kinetic hits, though it becomes less effective at shielding the second layer from heat. The second layer is a metal alloy, strong but not particularly amazing relative to other nations' equivalents.

-- Shielding: Varsovian military vessels use plasma shielding. This combines electromagnetic shielding with a layer of suspended plasma forming a “surface.” The electromagnetic energy can repel metal projectiles and disrupt energy beams, while the plasma gives the shield mass to resist kinetic weapons EM doesn't affect, such as neutral projectile beams.

-- Missiles: Both short-range and long-range missiles are major components of Varsovian fleet doctrine. They are all made primarily of ceramics, with semiconductors and other metals as necessary for electronic guidance, to minimize the effect of enemy electromagnetic shields. They are equipped with a range of warheads, of which three are notable: 1) Plasma warheads, standard fare for their sheer destructive power, 2) EM warheads, which can disrupt enemy systems if they explode close enough even without physically hitting a hull, and 3) Chemical/Bio warheads, usually attached to heavy missiles meant for planetary bombardment but also used in smaller missiles fired into enemy hull breaches to eliminate enemy crews without destroying the ship.

-- Particle Accelerators: Alongside missiles, these are the primary weapons of the VRN. As a long-time backbone of the military, they benefit from technology that has optimized their energy-efficiency, more efficient than many lasers though still energy-intensive. Plasma beams are the most common simply because they do the most damage to hulls. Neutron beams are also fairly common, packing a heavy kinetic punch and unphased by electromagnetic shielding. In addition, Ion beams are often used to disable enemy vessels without destroying them.

TERRESTRIAL ARMY DETAILS

Royal Peacekeepers

Officially, Varsovia does not have an army for offensive campaigns. In practice, however, it is easy enough to designate foreign territories as rightful patrimony and enemy soldiers as lawbreaking rebels. Nonetheless, the Varsovian Peacekeepers are indeed a force mostly geared for defense. Some 2/3 of the army is kept in reserve on system of rotations, while the bulk of active-duty personnel function de facto as a heavily-militarized police force. Only the 2 billion-strong Sky Patrol, the Peacekeepers' all-noble branch comprising air forces and gunship-based ground assault forces, could be considered ready for a true offensive campaign.

Varsovian Special Operations Police

The Crown's most elite and secretive military branch, the VSOP make very adaptable special forces. Their speed and stealth make them useful as counter-insurgency troops and commandos, but they also boast major conventional battle advantages such as true power armor (as opposed to bulkier battle-suits), personal electromagnetic shielding, and the pinnacle of high firepower miniaturized into infantry-portable weapons. Like the Drop Patrol, they rely heavily on air transporation, but with less grandiosity and more subtlety. In short, VSOP hits very hard, very fast, very precisely, and very quiet.

VSOP is not a noble-only force. It integrates all species into its ranks, making use of their varied natural advantages where applicable. Historically, VSOP was instrumental in securing the early beachheads in revolutionary-controlled territories.

-- The Serf Levy: Military service is a necessary element of the sacred contract between serf and lord. The usufruct right to land or capital comes with the duty to defend it in times of danger, as every self-respecting serf naturally accepts. Enemies of Varsovia best be wary of threatening the lands and homes of its subjects, lest they find themselves confronted by these millions of patriots!

-- The Yeoman Peacekeepers: These bravest of Varsovian free peasants have volunteered to defend King and Country with their lives. After four months of intensive training in their local garrison, they are issued a wide variety of modern military weapons, as well as a writ of Crown permission to bear arms and maintain order in the realm.

-- The Sky Patrol: While the Peacekeepers protect the people and values of Varsovia on the ground, these extraordinary aviators keep the air clean of threats foreign and domestic. But as gentry familiar with the spirit of meritocracy and friendly competition, the Sky Patrolfolk have also organized their own battle-suit ground divisions known as the Drop Patrol.

-- The Varsovian Special Operations Police: Among the brave souls who join the ranks of the Royal Peacekeepers, those of the greatest talent and character are selected for the Special Operations Police. When the most dangerous criminals arise, whether ruthless syndicates exploiting honest subjects or brutal foreign agitators threatening the lifeblood of commerce, Varsovia can count on these exemplary soldiers to restore order with maximum efficiency.

-- The Yeoman Peacekeepers: These bravest of Varsovian free peasants have volunteered to defend King and Country with their lives. After four months of intensive training in their local garrison, they are issued a wide variety of modern military weapons, as well as a writ of Crown permission to bear arms and maintain order in the realm.

-- The Sky Patrol: While the Peacekeepers protect the people and values of Varsovia on the ground, these extraordinary aviators keep the air clean of threats foreign and domestic. But as gentry familiar with the spirit of meritocracy and friendly competition, the Sky Patrolfolk have also organized their own battle-suit ground divisions known as the Drop Patrol.

-- The Varsovian Special Operations Police: Among the brave souls who join the ranks of the Royal Peacekeepers, those of the greatest talent and character are selected for the Special Operations Police. When the most dangerous criminals arise, whether ruthless syndicates exploiting honest subjects or brutal foreign agitators threatening the lifeblood of commerce, Varsovia can count on these exemplary soldiers to restore order with maximum efficiency.

Serf Levy Defending the Homeland:

Yeomen Peacekeepers on a Counter-Insurgency Mission:

Drop Patrol Gunship:

Drop Patrol “Infantry” Suit:

Drop Patrol Heavy Suit:

Drop Patrol Artillery Suit:

VSOP Infantry in Conventional Battle:

VSOP Dropship:

Yeomen Peacekeepers on a Counter-Insurgency Mission:

Drop Patrol Gunship:

Drop Patrol “Infantry” Suit:

Drop Patrol Heavy Suit:

Drop Patrol Artillery Suit:

VSOP Infantry in Conventional Battle:

VSOP Dropship:

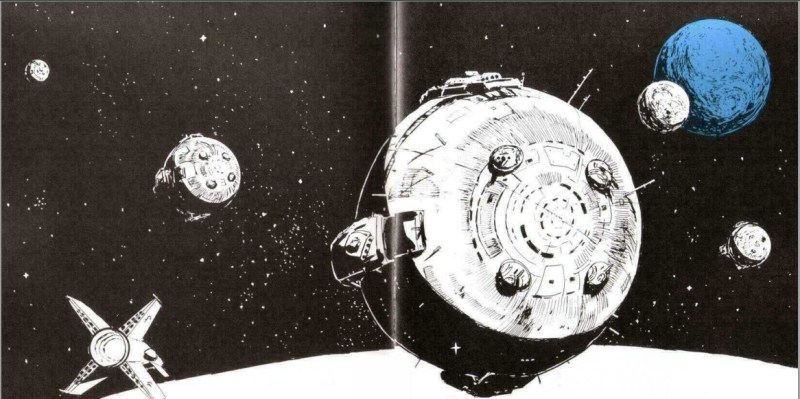

NAVY DETAILS:

Varsovian Royal Navy

Traditionally an all-noble branch of the military, as the VRN grew it was forced to integrate peasants simply to fill its ranks with the necessary technicians and crewfolk. They even fill positions as lower-level officers, though higher up the command chain remains exclusively Shravian. As the unquestioned centerpiece of Varsovian military doctrine, the Royal Navy is by far the best-equipped branch of the military.

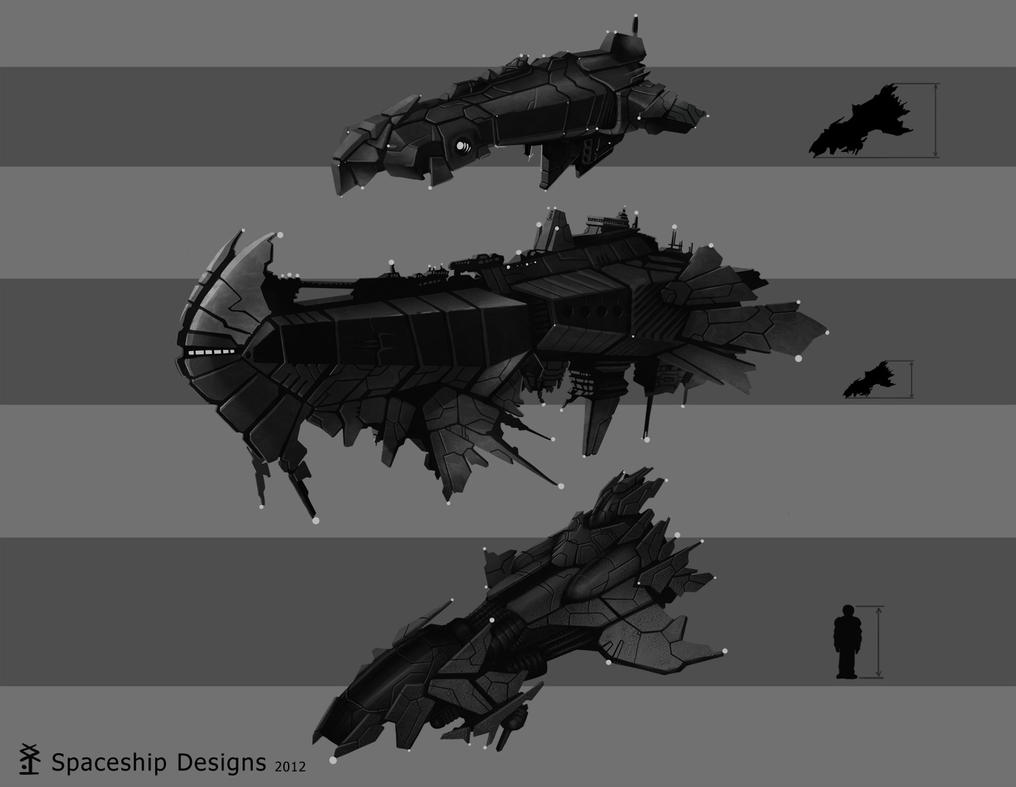

VRN Knight Battlecruiser: The most common of Varsovian starships, the Knight is a versatile vessel. Each carries approximately 1 Ion Cannon, 2 Neutron Cannons, and 2 Plasma Cannons as well as 4 short-range missile pods – each with a capacity of 100 medium-duty missiles. The Knight also carries an impressive array of point-defenses in the form of 30 mini Neutron Cannons and 12 mini missile pods – each with a capacity of 300 missiles.

VRN Hussar Assault Battery: Accompanying Knights in the Varsovian “front attack line,” the Husaria is the absolute peak of heavy forward firepower. It carries five Heavy Plasma Cannons, a gargantuan Dorsal Plasma Cannon built into its hull, two heavy short-range missile pods carrying 200 heavy-duty missiles each, and four short-range missile pods of the Knight variety. The Husaria lacks point-defenses, and thus relies heavily on Knights for protection, but also has very heavy armor and shielding to compensate.

VRN Onager Bombardment Cruiser: The backbone of the VRN's “holding line,” carrying some twelve 50-capacity long range missile pods as well as a single range-optimized Heavy Plasma Cannon. With such a heavy weapons load for a relatively small ship, it can support only modest armor, shielding, and point defenses. Onagers must rely on Bastions for protection.

VRN Bastion Dreadnought: Bastions are the command ships VRN fleets as well as the anvils to the Hussars' hammers. Their size, armor, shielding, and vast point-defense networks easily outclass every other ship in the Varsovian arsenal. They also carry advanced sensors for long-range targeting and stealth detection, which is continuously relayed to nearby vessels (most notably the Onagers). Bastions also carry Electronic Warfare Centers, where the VRN engages in cyber battle to disrupt enemy communications/sensors and protect their own. Yet, when it comes to direct ship-to-ship armament, the dreadnought is less exceptional. Simply because of its sheer size, it still mounts an impressive 2 Heavy Plasma Cannons, 4 Heavy Ion Cannons, 4 Heavy Neutron Cannons, and 14 Plasma Cannons. But it lacks anything equivalent to the Hussar's Dorsal Cannon, and it carries no anti-ship missiles.

VRN Tower Strike Transport: About half the size of a Knight, the Tower is the VRN's smallest front-line combat vessel. It carries little in the way of direct weaponry, only eight Mini Neutron Cannons and a single mini-missile pod for point defense. To compensate, it boasts disproportionately powerful frontal shielding and the fleet's most impressive combination of speed and maneuverability. Each Tower contains four Heavy Dropships and twelve Fighter-Bombers, all capable of both space and atmospheric flight. The Heavy Dropships each hold 50 marines, and the Fighter-Bombers each carry two small plasma cannons and eight missiles.

VRN Space Mine: A recent, experimental design in a stealth warship. The Space Mine is well-armored but has only light shielding, as its stealth systems require much energy. For the same reason, it lacks particle beams and is instead packed with three-hundred heavy short-range missiles. Due to the plating requirements of its stealth system, these missiles do not come in traditional pods, but are rather packed underneath the hull in a system of tubes that fire out of eight possible openings. The system is optimized to release these missiles very quickly, up to two missiles per second per opening.

VRN Hussar Assault Battery: Accompanying Knights in the Varsovian “front attack line,” the Husaria is the absolute peak of heavy forward firepower. It carries five Heavy Plasma Cannons, a gargantuan Dorsal Plasma Cannon built into its hull, two heavy short-range missile pods carrying 200 heavy-duty missiles each, and four short-range missile pods of the Knight variety. The Husaria lacks point-defenses, and thus relies heavily on Knights for protection, but also has very heavy armor and shielding to compensate.

VRN Onager Bombardment Cruiser: The backbone of the VRN's “holding line,” carrying some twelve 50-capacity long range missile pods as well as a single range-optimized Heavy Plasma Cannon. With such a heavy weapons load for a relatively small ship, it can support only modest armor, shielding, and point defenses. Onagers must rely on Bastions for protection.

VRN Bastion Dreadnought: Bastions are the command ships VRN fleets as well as the anvils to the Hussars' hammers. Their size, armor, shielding, and vast point-defense networks easily outclass every other ship in the Varsovian arsenal. They also carry advanced sensors for long-range targeting and stealth detection, which is continuously relayed to nearby vessels (most notably the Onagers). Bastions also carry Electronic Warfare Centers, where the VRN engages in cyber battle to disrupt enemy communications/sensors and protect their own. Yet, when it comes to direct ship-to-ship armament, the dreadnought is less exceptional. Simply because of its sheer size, it still mounts an impressive 2 Heavy Plasma Cannons, 4 Heavy Ion Cannons, 4 Heavy Neutron Cannons, and 14 Plasma Cannons. But it lacks anything equivalent to the Hussar's Dorsal Cannon, and it carries no anti-ship missiles.

VRN Tower Strike Transport: About half the size of a Knight, the Tower is the VRN's smallest front-line combat vessel. It carries little in the way of direct weaponry, only eight Mini Neutron Cannons and a single mini-missile pod for point defense. To compensate, it boasts disproportionately powerful frontal shielding and the fleet's most impressive combination of speed and maneuverability. Each Tower contains four Heavy Dropships and twelve Fighter-Bombers, all capable of both space and atmospheric flight. The Heavy Dropships each hold 50 marines, and the Fighter-Bombers each carry two small plasma cannons and eight missiles.

VRN Space Mine: A recent, experimental design in a stealth warship. The Space Mine is well-armored but has only light shielding, as its stealth systems require much energy. For the same reason, it lacks particle beams and is instead packed with three-hundred heavy short-range missiles. Due to the plating requirements of its stealth system, these missiles do not come in traditional pods, but are rather packed underneath the hull in a system of tubes that fire out of eight possible openings. The system is optimized to release these missiles very quickly, up to two missiles per second per opening.