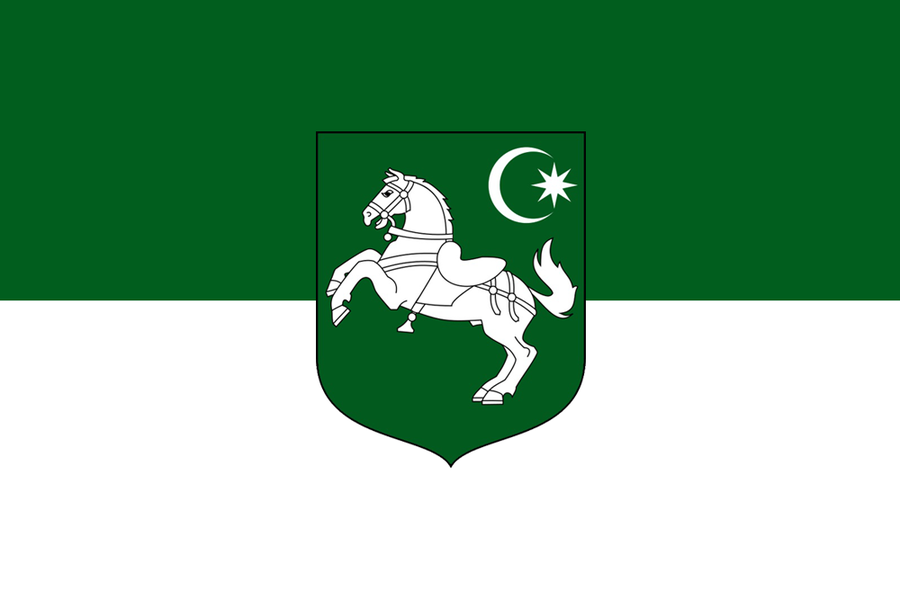

Grand Duchy of Cordonova

Nation Overview

The Grand Duchy of Cordonova is a massive confederation of seven semi-autonomous duchies stretching from the imperious Nordöldt Range in the east to the jeweled capitals of the western sea, bridged by the “Veldt”, a vast steppeland plied by doughty horsefolk. Although the grand dukedom has remained in the hands of House Valbe for generations, it is a pliable office, awarded by election of the Notables, a parliament of influential aristocrats, landholders, and merchants. Each of the seven dukes of Cordonova pledge fealty to the Valbi, though their knees are not always easily bent. The Grand Duchy is a tapestry of variegate cultures, and six different languages are spoken within its borders, though Cordonné, the autochthonous tongue of the western duchies of Valbe and Péy, remains the lingua franca. Before the light of the Ambrusian Church came to these lands, they were convulsed with incessant tribal and factional warfare. While the Church provided the glue by which the dukedom could be forged, it was administered by fire and blood; now, although three hundred and ten years have elapsed since King Volmer of Ruri and the Veldtish Counts clashed beneath the open sky, memories abide far longer than the ephemeral lifetimes of men. While Grand Duke Lirian carouses and whores in the arrased halls of Léonne, unseen forces conspire to bring about his demise, and the downfall of House Valbe.

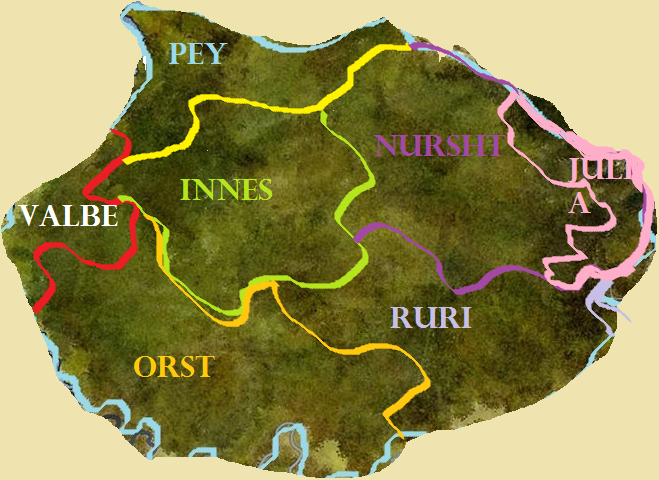

Geography

The Grand Duchy is home to a startling variety of landscapes and biomes.

In the far east, the grand Nordöldt Range (which grants the region its name: Nordöldtas) rises to assault the heavens, thronged about its base with deep timber forests of pine and cedar, which whiten with ponderous snowdrifts in winter and flame red in autumn.

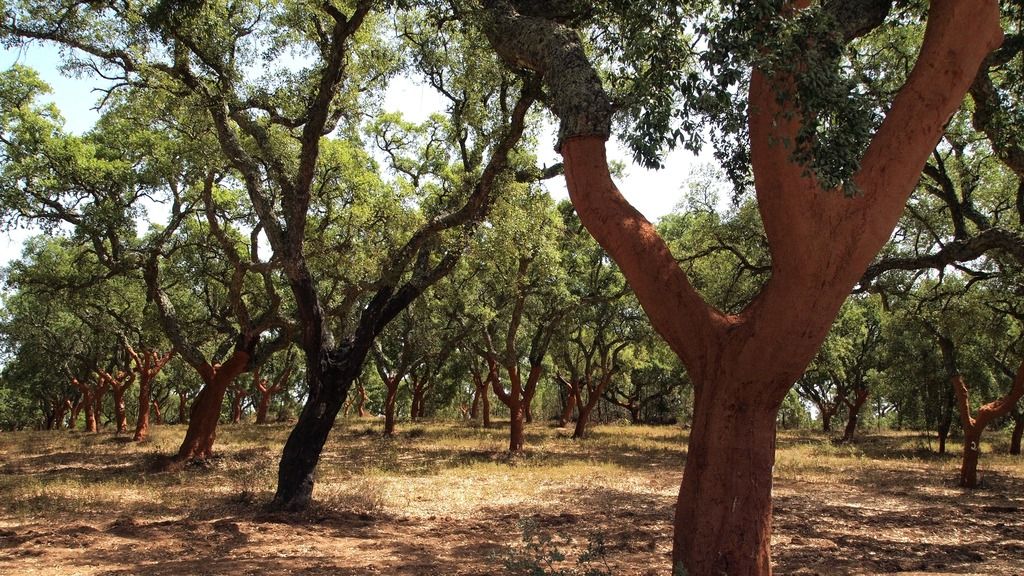

Far to the west, along the jeweled coasts of Péy and Valbe, collectively known as Laübrunne, or more colloquially, The Harem, the climate is decidedly warm, with chalk-white cliffs and rolling hillocks lined with cork and olive trees.

The southern duchies of Örst and Ruri, known together as Unterham, are yet warmier and drier, yet marked by consistent changes of elevation, and thus, of clime: one valley might be almost desertic, filled with cypress trees, while another might be blanketed with snow even in the summer sun and peopled by pine. These vast climactic and altitudinal variations have historically made the region difficult to rule, and even more trying to conquer.

However, the most quintessential of Cordonovan landscapes would be the vast steppelands of The Veldt, a broad grassland swept by the wind and often frigid in the winter months, broken here and there by low-lying ranges; from the Veldt arose the grand equestrian tradition of the Grand Duchy, the backbone of its martial accouterments.

History

The Grand Duchy as it is known today was forged when the last of the Pretenders, King Volmer of Ruri, a heathen who professed the Three-Head God Böl, was defeated by the Veldtish Counts, a confederation of Fiorentinan potentates who sought to smash the idolaters in the name of the Saint. This confederation would serve as the mold upon which the Grand Duchy was based. The house of Volmer was put to the sword, and the pastured expanses of Ruri stained with blood and fire. In the afterglow of the bedlam, however, an argument arose over who of the lords would assume control of Ruri herself. Thus was convened the first council of the Notables, a grand assembly of the noble houses of the Veldtish Counts, who eventually declared that House Yarbos of Julla should receive the conquered lands. At this same convention, the Grand Duchy itself established, and the mantle of Grand Duke awarded to Odo of Duchy Núrsht.

Before, tribal and factional conflict had harangued the region. Raiders of the Unterham were feared and reviled, and the-then Kingdom of Valbia made designs on Reheba (hostilities were ended by marriage pact). What would be the Duchy was divided by bonds of sovereignty, culture, and language, and it was a scoffed at notion that this war-like region of horsemen and bearded mountaineers and poetic seafarers should ever constitute a united sovereign entity. Religion, it seems, is the great equalizer.

The Laübrunnids of Péy and Valbe, following the formation of the Grand Duchy, gained much from contact with the surrounding Fiorentinian world. Goods from the East flooded the ports of Léonne and Ondaz. Always a rich but martially inferior region, the Laübrunnids grew fat with luxuries, and new arms and armaments were introduced into the duchies. The rising influence of Laübrunne precipitated the ascension of what some would call the "Licentious Captivity", the domination of the Grand Dukedom by the West. This "Captivity" endures to this day, as firearms ascend to fashion in the Fiorentinian world.

But, the Laübrunnids have never been known for their strength in numbers. The military prowess of the Veldtish Dukes remains the spine of the Cordonovan martial tradition and as of yet hold the most voting power in the congress of the Notables.

Society

Cordonovan society is striated into five essential “castes”, which themselves are further delineated—these being the serfs, the septád (a class of mounted warrior common in the Veldt who often serve as the heads of families or leaders of horse in their lords’ retinues), the incipient burghers, the clergy, and the landed nobility.

The serfs serve as agrarian laborers, of course, and are above all noted by their religious piety (instilled rather insidiously by the Church fathers) and their poverty, although in recent decades several advances have been made towards a more equitable system for them, most notably by such reformers as Countess Jaleš of Pojačs.

The septád (which translates to “Horse-uncles” in Old Hőltíg, the language of the Holtí people of the ancient Veldt) once perhaps secondary in import only to the aristocracy, have, following the gradual inflammation of Fiorentian fervor and the introduction of newfangled military technologies, somewhat diminished in stature in the Grand Duchy. However, their tradition is fertile, harkening back to the tribalism of centuries past. Previously, the septád served as the representatives of various homóz, or “totems”, families within tribes which brought tribal grievances to the Grand Hetman and served as his own body-khans, fighting alongside him on the field of battle. They were entitled to wear indigo-stained lamellar and red ermine, some of the most highly prized luxuries of that epoch. New technological innovations, countering the heavily armored knights which have dominated for centuries, however, might make their ilk obsolete, or at the very least little more than a formality in future.

The burghers, the merchant class of guildsmen which has come to prominence throughout the Antovan continent, has arrived in the Grand Duchy as well. In particular, the burghers of the Laübrunne duchies have risen to wield a great deal of influence in Cordonova, with their banks and far-ranging galleons. However, the Nordöldten burghers, with their vast lumberyards, and the Velditsh, with their horsemongers and wide river boats, likewise turn a profit. Only in the sparsely populated and isolated Unterham has yet to be capitalized upon, despite its proximity to the commercial capital of Turchina.

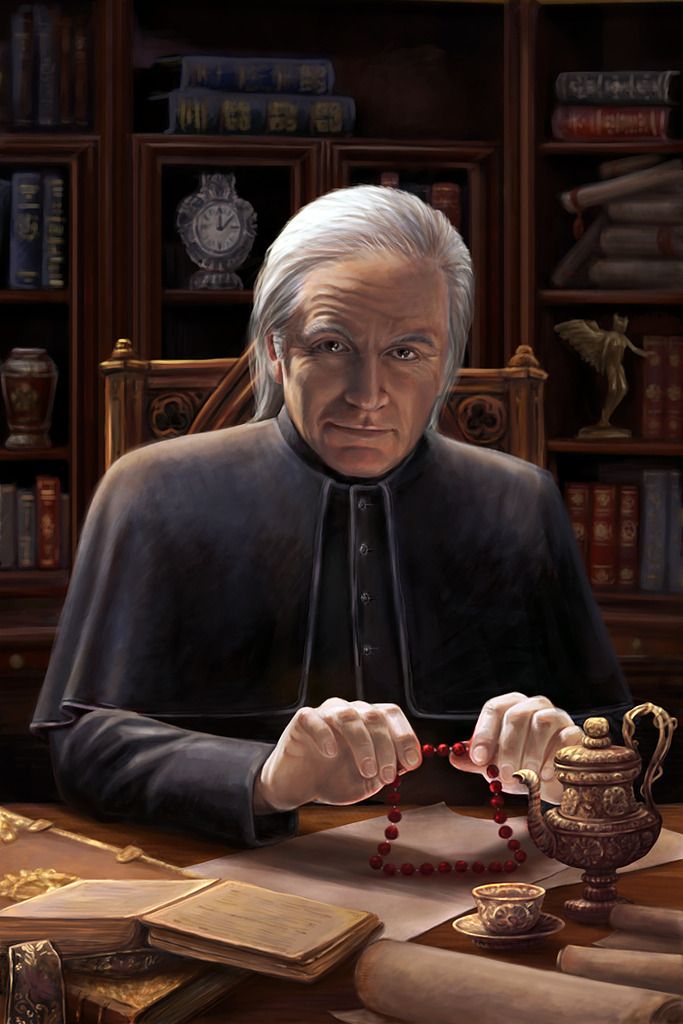

The clergy themselves play a more diminished role than in other Fiorentian kingdoms of Antova, but a vibrant one nonetheless. Particularly in the Veldt, with its vast population of grain-growing serfs, they are of critical importance. However, in each of the various regions of the Grand Duchy, it is a different matter. For instance, although the populace is nonetheless pious, the clergyfolk of the Laübrunne are marked by their tendency towards lavish excesses, and, oftentimes, corruption—though this is in part a consequence of the influence of the ruling castes. In the Unterham, however, oftentimes the curates are nearly paupers—the geographical difficulties of the region have multiplied the vagaries of proselytization, and many pagan enclaves yet exist secreted away in the high valleys and dry expanses of the scrublands. Many Unterhalt potentates, it seems, have merely adopted the Fiorentian faith simply as a matter of course and not one of belief, despite the elapse of three centuries since its introduction. In Nordöldtas, the clergy have faced similar difficulties, although the efforts (often aided by pyres) of Duke Ortlí “The Priest” a century and a half ago seem to have rooted out the pagan for the most part.

Finally, the caste-nobility occupy the pinnacle of the pyramid of Cordonovan society. Within the framework of this cast exists a further striation, the petty nobility. These are nobles who have bought their title, or have been recently landed. Exemplars of the petty nobility often include members of the septád, who buy up land beyond their own ancestral allotments and serve their Dukes as margraves, hetmans, or khutorids. Of course, regardless of locality, these newly-made men are singularly reviled by old-blooded aristocrats, though they do not chafe at their services when their fealty is useful to them.

Economy/Industry

The Grand Duchy whose wealth is disproportionately inclined towards the coastal duchies of Péy and Valbe due to their monopolization of commerce with foreign entities, particularly the Fiorentian nations of Reheba and Mille-Sessau and, perhaps egregiously, with the heathen Timluks. The Laübrunne duchies themselves produce such products as grape and apricot wine, olive oils, cork, and are amply outfitted with arable and fertile lands for the cultivation of broad beans, chickpeas, foxtail millet, and wheat, the staples of the Laübrunne diet.

Although some land routes from the north cross the Veldt, trade is most commonly conducted by means of riverine transit on the plains, or by laden wains which take the long road to Ondaz and Léonne. Few true roads cross the Veldt, and indeed, one might note that the region’s numerous river systems serve as its principal arteries as well.

The monolithic Nordöldt Range bars the conduction of commerce from the east to the Julla; however, the vast timber forests that throng the foot of the mountains provide ample logging opportunities, and rich mineral wealth substantial ore. Thus, the Nordöldten are fine metalworkers, and their steel weaponry and silversmithery are some of the most highly sought after exports of Cordonova; furthermore, Nordöldten lumber fuels the grand Laübrunne shipyards.

The Unterham produces some goods, such as dates, citrus fruits, peppercorns, fine furs, and scented woods, the wealth of the land has yet to be truly seized upon. Some land trade routes convey these products to the more northerly capitals, and down the river to the coastal city of Ülmo (a popular stopover port-of-call before Ondaz and Léonne further up the coast), however, and the relative lack of production in the region leaves it ripe for the development of newfangled industry, despite the geographical pitfalls.

Military

Military

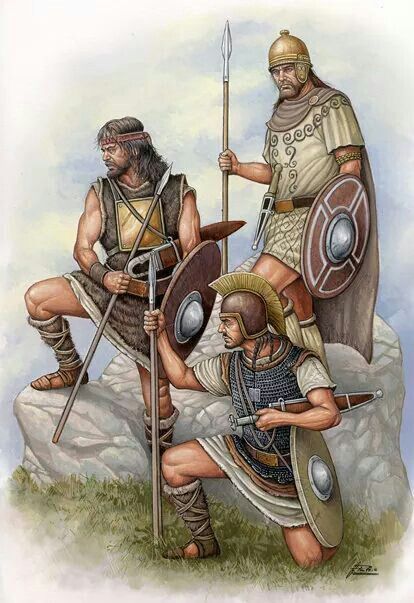

The Cordonovan military is one dominated, as one might expect, by cavalry. The bulk of the Grand Duchy’s military derives from the levies fielded by the Veldtish duchies of Innes and Núrszt, whose fearsome horsemen have humbled many an over-ambitious commander in centuries past. The charge of the Núrmen at the Battle of Hágwen Swale, for instance, was one of the largest, and deadliest, of recorded history. The Veldtish horsemen are renown for their heavily ornamented armors, lavish surcoats, and pilloried destriers. Although now known for the lance and sabre, in ages past, and to a lesser degree in the modern day, the horse archers of Innes struck terror into the heart of many an Antovan commander.

With the advent of the arquebus, pike, and tercio, however, newfangled stratagems have become the norm of Antovan warfare. Although the Cordonovan cavalry still proves a doughty foe, the military, particularly the Veldtish and the Nordöldten, have had some difficulty adapting. The Laübrunne duchies, with their deep coffers, and with a much smaller populace than the rest of the Grand Duchy, has had need of fielding mercenary forces of landsknechts, tercios, pikemen, and arquebusiers to bolster their otherwise scant levies of men-at-arms, crossbowmen, and armored knights.

The Nordöldten, in their steep mountain fastnesses, have never proved as able horsemen as their Veldtish neighbors. Rather, they are known for their powerful armored footmen, armed with long axes, halberds, and longswords, alongside fierce bowmen and crossbowmen and fleet sappers. The workshops of Munten, at the urgings of their Laübrunne clientele, have begun to produce the intricate machinery of the matchlock; however, the actual adoption of musketeering has been slower to affect, due to the absence of conflict in the region.

The Unterham, like the Veldt, was once one of the more densely populated regions of Cordonova. However, the great wars of centuries past and a string of famines which incited a number of migrations have depeopled it. Nevertheless, The Unterham knights and men-at-arms are renown for their ferocity and, oftentimes, their brutality. The undulating nature of the land of the Unterham makes ambush a simple thing, and the thick-walled battlements of their keeps made the pacification of Volmer and his confederates one of the most costly and violent wars in Cordonovan history. Although still attuned to a rapidly waning manner of warfare, what the Unherham levies lack in numbers and technological innovation they make up for in unfettered zeal.

Dramatis Personae

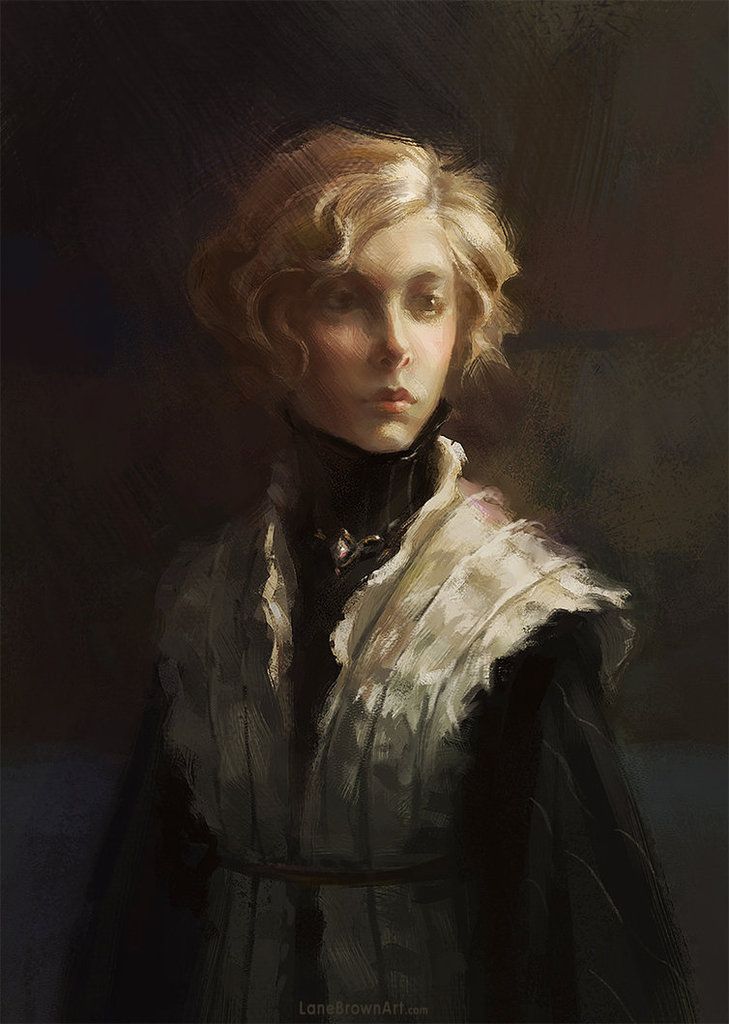

In the Duchy of Valbe

Household, Courtiers, and Vassals of House Valbe

In the Duchy of Innes

Household, Courtiers, and Vassals of House Dorcaš

Citizens of the City of Letwijs

In the Duchy of Örst

Household, Courtiers, and Vassals of House Imgarda

In the Duchy of Julla

Household, Courtiers, and Vassals of House Kallebjor

Despite his houses influence and riches very much an able Seaman, and by now Maestro di Marina, commander of Turchinas War Navy, in addition to his houses sizeable own naval force.

Despite his houses influence and riches very much an able Seaman, and by now Maestro di Marina, commander of Turchinas War Navy, in addition to his houses sizeable own naval force.

.

.

.svg/revision/latest?cb=20120513021903)