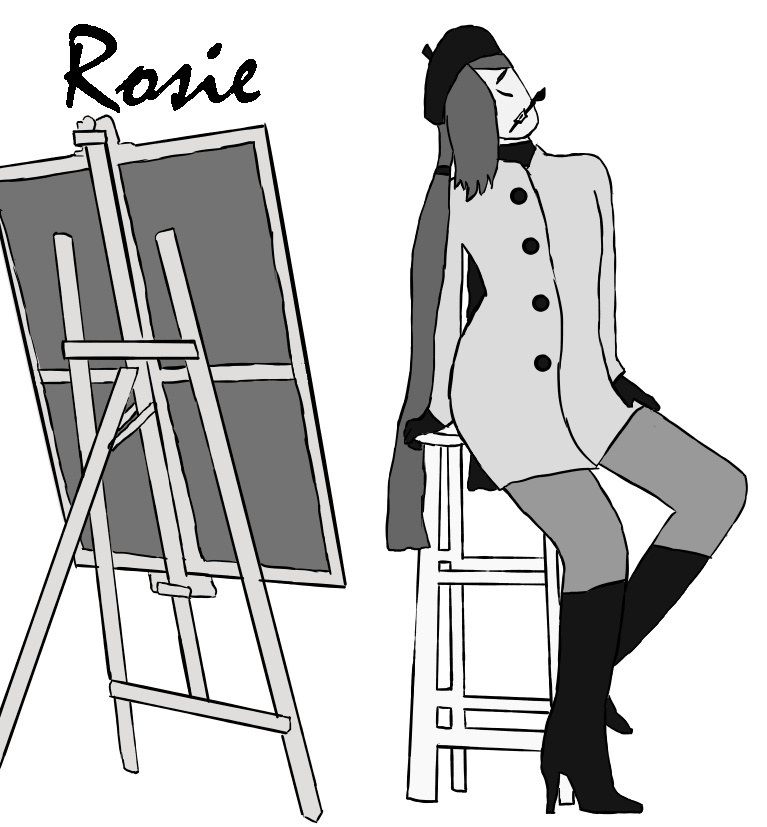

APPEARANCE A tall, unsmiling woman who breaks six feet by an inch or so, Verga does not put off the friendliest sort of appearance. Her teardrop-shaped face is solemn and unrevealing, and her sharp, almond eye has a way of telling you, no, she would not laugh at that joke, so don’t try. Verga’s skin is somewhat light, and her body is visibly strong—her massive reserves of life energy have prolonged her youth, appearing more like a woman in her early forties, or maybe late thirties, though her eye has a certain weariness to its lined and lidded gaze that does not match her appearance.

The siniydusha condition that Verga was born with stained her hair, eyes, eyelids, and nails a valley lily shade of blue. Her hair falls nearly shoulder length, and the bangs over her face are swept carefully to the side, hiding the place where her left eye would be. Behind the hair, an eyepatch covers up an empty socket—you give up some things, chasing power. Verga’s fingernails are all filed into long, sharp points, and her fingers are thin and calloused from years of work.

On the surface, Verga's wardrobe is rather simple. Clean black turtleneck jumpers and white cargo-pants. Very efficient. Her boots are dark and hardy as well, though maybe a bit sleeker than functional, with heels a bit higher than would be fitting for a martial artist and survivalist. Her belt is also notably nice, dark with a round brass disc to buckle the warm leather. She also often wears a dark, heavy greatcoat, with sleeves and a collar marked with subtle but intricate floral designs. Bits and pieces of her hidden vanity, always poking through.

PERSONALITY TRAITS ■ Cold

■ Proud

■ Willful

■ Unsympathetic

■ Single-minded

■ Introverted

■ Socially awkward

■ Superstitious

■ Power-hungry

■ Merciful

■ Commitment issues

■ Uncomfortable around children

BACKSTORY & MOTIVATION Verga could not have shown you her hometown on a map. She could not tell you the name of the lake below the village, the mountains that blocked out the morning sun, or the woods that surrounded her childhood on all sides. Her world was nameless, one made up of plowing snow and dark forests, and fairy tales whispered over crackling fires. The village was the only thing there was—that, and the bristling wilderness.

Verga’s education had no room for science or history. She learned how to cut down trees and how to make camps, how to kill animals and light fires, how to keep the frostbite from turning her fingers and toes into blackened corn-husks. She learned basic math and literacy so outsiders couldn’t trick her, and she learned to distrust people, and to distrust nature, because both would always be looking for ways to gain the upper hand. However, if given the choice, she felt most at home in the forest, preferably in the wintertime, when the snow made everything peaceful and hushed. One day, far in the future, she would emerge onto the world stage as a renowned martial artist, but even as an adult with years of experience in the outside world, she could never feel comfortable in urban areas, or among crowds.

In Verga’s world, your worth was determined by the weight you pulled, and no one pulled more weight than Verga Ilgraven. Though her neighbors were never the affectionate type, and most exchanges, even with family, were short and gruff, she was always appreciated for her natural abilities. Verga had been born with a unique condition, siniydusha, the blue ki, which endowed her with enormous innate strength, and grew faster than any normal ki. By the time she was sixteen, Verga could carry more firewood than any man in the village, and could endure biting cold that would glue even the hardiest lumberjack to the fireplace. Each year her strength swelled. But it was never enough; the more powerful she grew, the more Verga wanted. During excursions, she would stray farther and farther into the wilderness. If she could, she stayed away from the village, which began to seem unbearably small. One day, when she was 19, a hunting expedition took Verga to the very edge of the valley. Without giving it any conscious thought, she just kept walking.

For over a year Verga traveled east through thick, unforgiving wilderness. She was searching for something, and she didn’t know what, not exactly, but she knew she wouldn’t have found it back in her old valley. She fought off beasts, and she fought off the elements. Even with her prodigious strength, it was a grueling ordeal. More than once Verga sat beneath the trees, staring up at the sky, dizzy with exhaustion and starvation and certain she was going to die.

The handful of towns she passed slowly filled in the gaps in her knowledge of the world—she was in Siberia, which was a part of Russia, and, the few times her power was brought to light, they called her strannik: a Nomad. Eventually, after months in the wild, she reached the Chinese border.

After a run-in with border patrol, Verga would embark on a two-week string of misunderstandings, miscommunications, and several fights, before she was ultimately scooped up by a local tai chi master. He took notice of both her raw potential and her lack of affiliation to any competing nation or martial arts school, and was quick to recruit her.

Verga’s new master would aid her in obtaining Chinese citizenship, and teach her the local languages. And during the next three years, she found exactly what she had wanted for so long—training, purpose, and power. She would study tai chi and, eventually, arnis, and begin to learn more and more about this strange new world beyond Siberia.

Tai chi did not agree with her at first, Verga’s hard, inflexible personality making the fluid, changeable martial art a frustrating challenge. Years passed. Verga worked, and worked, and at some point that work paid off. Her blue ki grew, ravenously. After only a shocking five years of training, she used her natural gifts to equal her master himself. Success met her in multiple local tournaments, and she was soon something of a small celebrity. Pride, power, success—Verga had all of these in no small supply, and she was drunk on them. She even began developing her own martial arts style—tai chi and arnis weren’t enough, it seemed. As with everything in life, Verga would not be satisfied with what things were when she could see so clearly what they could be.

Verga was not stupid, however, and sometime after leaving her old workshop she realized it took more to survive in the outside world than flashy martial arts. With this in mind, Verga enrolled in a local university at the age of 25.

It was at school that she became acquainted with Runsu Ryuga, a Japanese exchange student. Verga rarely had strong feelings when it came to other human beings who, in most cases, either confused or alarmed her, but she wasted no time in deciding she felt, openly and mightily, a strong hatred for this boy.

Runsu was from money, and it showed. His clothes, his laptop, his car, and of course his bragging. Like Verga, he had quite the ego, though where Verga was reserved, and preferred to speak with actions, not words, Runsu was all talk. Unfortunately, he too was an aspiring nomad, and Verga soon found he had the bite to back up his bark.

Runsu would be the first person to ever challenge Verga. Sometimes they sparred, and sometimes Verga would win. Her raw ki reserves providing a slight edge over the skill-oriented Runsu, but if she did beat him, she would be challenged for it. Often, Runsu would win. These wins burned the skin of her pride like frostbite. When he mocked her for her strange habits, her accent, her grades, it killed Verga to know that any punch she threw at him could be matched by one just as strong.

In academics, Verga was hopelessly behind her other classmates. While Runsu was only a middling student, he was studious enough to stay ahead of her, and his successes in the face of her failures frustrated Verga in a way only her early years in tai chi could rival. She channeled her anger into her work, and sometimes into her fists during sparring matches. The rivalry between Verga and Runsu would reach a peak during one clash in the spring semester when, after gaining the upper hand, Verga lost her temper, and her rival was very nearly killed. All Verga’s frustration poured out of her just then, her confusion at the strange new world she lived in, her hatred for the industrialized inner city, her frustration with her own academic progress, her loathing of Runsu—all of it. Eventually, she pulled back, not knowing or caring if Runsu was still alive. Then, she did something she couldn’t have explained, just like she couldn’t have explained why she kept walking all those years ago, when she left her village for good. Picking him up, Verga took Runsu to a local hospital.

She allowed doctors to extract her own ki for healing. For some reason, the thought of him dying, and her being responsible, drove a deep, uncomfortable spike through her belly.

She was there when he woke up. There wasn’t much to say. Uncomfortable, unhappy, half-wishing she had left him to die, Verga left. She would return only once afterwards, to drop off a bag of pao after the local streetcart accidentally gave her extra. Later, Runsu confided in her that she was the only person to visit him while he was hospitalized. Parents were too busy, he said. What about your friends? she’d asked. He shrugged.

It wouldn’t be long before Verga realized the sickly feeling that had been following her since the fight was guilt. She felt guilty. It was unfamiliar, ugly territory she wanted nothing to do with, but apparently that wasn’t an option. Runsu, for his part, seemed more reserved around her. There weren’t any more taunts, at least.

It took time, but eventually the two took to talking. Runsu, despite whatever he said before, was quickly fascinated by Verga’s stories of her upbringing, and listened raptly to her descriptions of traditional Siberian fairy tales and folklore. Verga eventually found Runsu was the only person she was comfortable asking simple questions that, prior, she had been too embarrassed to ask her master. They began to confide in each other. Their old egos, both injured by that unhappy fight, began to swell again. They trained together, they studied together, and before long they were dating.

It felt, to two young adults, both in their own ways unfamiliar with the realities of the outside world, that they were at their peak, the top of the world. Their feats in tournaments brought them modest fame, but to them, modest fame felt like the most glorious thing in the universe.

Both were interested in refining their own, unique takes on martial arts, and their arguments over whose was better were ultimately settled by a strange, alien thought—what if we had a child? They could teach that child everything they knew. A legacy worthy of their talents (and egos), a trophy that would combine the best of both of them, together, united. This was only an idle thought, and they didn’t start actively trying for a kid so much as they stopped actively avoiding it. After all, even without condoms, it could be months, maybe even a year, before anything happened. But within two weeks, Verga was pregnant. Under encouragement from Runsu, she decided to follow through with it.

Not long into her pregnancy, Verga decided she wouldn’t return for her second year of university, and, with more than a little dissatisfaction, moved away from her more strenuous training. Runsu visited regularly. They had arguments over the child’s name, of course, both wanting a name to reference themself over their partner. Verga developed a bit of cabin fever, cut off from her training, but she endured. A checkup in the first trimester told them they would have a girl. A checkup during the second trimester told them their child would be born with Senshinōben.

It was a hereditary disease, one that drastically stagnates life energy. The baby would be pitifully weak from the moment she was born, with minimal ki reserves. If she was born at all, that is—the baby’s chance of survival was incredibly slim. A doctor hesitantly gave the option of an abortion, though this wasn’t something Runsu or Verga were ready to hear.

The two tried to talk about it, afterwards, but talking was never their strong point, even at the best of times. Learning their child would likely miscarry was nothing they were prepared for, and the two realized, privately and separately, that they were still very young, and there was so much outside of their abilities. They ended up arguing, and things probably would’ve gone better if they hadn’t said anything all.

Runsu didn’t visit as often, afterwards. From the way he talked when he did come by, you would think Verga wasn’t pregnant at all. He made no acknowledgement to her pregnancy, or the Senshinōben, and when Verga tried to press him he stammered and dodged and half-answered, and usually left early. Verga felt spite germinating inside her, like a spiky, armored creature squeezed between her organs, imagining Runsu going to classes, pretending she didn’t exist. She had always known he was the weak one. She began consulting with doctors on the possibility of an abortion, but something—stubbornness, fear, pride—held her back from committing. Still, while Verga stewed in her apartment alone—her belly round and full, her thoughts dark and unhappy—the ‘A’ word floated regularly through her head, though it always drowned below the sea of bitterness inside her before it could take root. She had Runsu’s number, but after the first few days, stopped texting, stopped calling, and would not respond to his few attempts to reach out.

As well-known and successful martial artists, the two had funds for extensive medical care and consultation. Eventually, it was decided to remove the baby by caesarian section, and place it in a heavily monitored sustainment tank. The surgery was a success, but the baby’s condition remained uncertain. Runsu avoided the hospital and Verga completely, and made no appearance. When the child finally stabilized, it was time for Verga to figure out what it would be called. Runsu failed to show, which Verga told herself was inevitable, but it didn’t stop the angry disappointment that flickered through her as she held her baby, alone. The child would take her surname, ‘Ilgraven.’ On the paperwork, feeling all those weeks of spite and anger come boiling over, Verga jotted down ‘Shippai’ in a burst of impulse. It was a Japanese word, her husband’s language, and it translated to ‘failure.’ Shippai Ilgraven would be her daughter’s new name. When Runsu found out, they shouted, then they fought. This one was a stalemate. Bloodied, bruised, Verga went to the car to take little Shippai out of the back seat, while Runsu stormed off.

If mastering tai chi was difficult, figuring out how to care for a baby was something else entirely. Verga was in and out of the house, constantly, always in need of new supplies, new clothes, new diapers. Shippai needed weekly check-ups, as her Senshinōben persisted in weakening the baby’s already delicate body. Verga had no idea what was right or wrong when it came to raising this tiny, squealing, fragile creature. Then, when Shippai was half a year old, Runsu returned. To Verga’s enormous surprise, he was back to apologize. She, of course, would not and could not forgive him, but he was there to help, and Runsu couldn’t refuse.

Runsu, likely with the thought of his own parents haunting his mind, did his best to stay by Shippai’s side at all times. He took off from university as well. Verga, who tried to care for the girl best she could, felt guilt for the second time in her life, this time over the child’s name, not to mention a certain amount of wounded pride over her daughter and heir carrying such a shameful moniker. Not that she ever said these things out loud, of course. Runsu was no longer the handsome boy she confided in, all those months ago. To the public, of course, it was a sweet little picture—two famous martial artists raising a child together. News of their strife would not reach the tabloids.

But as Shippai began to walk, and speak, the two began training her. Verga was determined to have this child throw off her name, her disease, to fight through and conquer it. Maybe if she did, all Verga’s past pain and confusion would be vindicated. Or, maybe, the guilt would go away.

Where Verga was a cold wall, pushing Shippai silently to grow no matter the cost and holding the girl at arm's length, Runsu was a constant fire, always telling her to do better, to be better, a fixture at Shippai’s side.

Meanwhile, no longer pregnant, Verga returned to her own training. To her frustration, the meteoric growth of her teens had slowed down, and her ki would grow only at a normal rate now that she approached her thirties. Still, it was good to be fighting again, seriously. But her martial arts seems hollow now. She continued to fine tune her blend of tai chi and arnis, which she now dubbed ‘Tikhiyvolna,’ the Tranquil Wave. She garnered attention in local tournaments, and imitators of her technique began to crop up, enough to gain her little experiment in martial arts proper respect as its own school, and, for herself, the title of Tikhiyvolna Master. But the limits of punches and kicks and self-defense seemed so small in the face of the struggles of the last few years. It was like being back in her old village again, surrounded by trees, unsatisfied by the smallness of the world. Verga hated that no matter her skill, no amount of martial arts could take away her powerless to situations like miscarriage, and broken hearts, and crying babies.

Whatever she did, whatever she said, Verga loved her daughter. She didn’t know what to make of that, of course, and, on some level, it disturbed her. But those few moments when she would play with the girl, show her how to build little towers out of wood blocks, or how to make twig dolls like the ones her parents made, or laugh while Shippai roared like a movie monster and knocked over her buildings—Verga was happy. But it didn’t make the guilt go away, or the pain, and having to deal with happiness and unhappiness at the same time felt more confusing than unhappiness on its own. And even if she loved her, love isn’t enough. If anything, it made Verga’s actions worse—a mother may be cold and heartless, and that’s a simple, understandable evil, but a mother who loved her daughter—she should’ve known better.

Verga and Runsu were not good parents. They pushed their daughter to reach the stars, and when she couldn’t, when the reality of the Senshinōben beat her back down, they, either consciously or subconsciously, would blame Shippai. Runsu would lose his temper and shout, Verga would go cold as stone and speak only curt, harsh indictments. Eventually, the tiny shred of goodwill that had built up with Runsu’s return fell away. They argued, and argued, and argued, and Shippai cowered on the sidelines.

When Shippai was seven, the two took their daughter to Japan, where Verga hoped to put her through survival training like what she endured in Siberia. On the way, as they often did, Shippai’s parents fought, and fought. In the airport. In Japan. Up in the mountains. While they walked the hiking trail, Runsu finally succeeded in pulling Verga’s trigger with a comment about her taking his future from him, and suddenly her icy sniping became vicious shouting. She ordered Shippai to wait for them by a bench on the hiking trail, and told Runsu that she was done. Done with him, done with Shippai, done with all of it.

That broke through his bluster. But what about Shippai? We can’t leave her here.

I can, said Verga. If you want to raise a child on your own, be my god damn guest.

She marched off down the path, and Runsu tried to follow her. By the mountain base, they came to blows. For the first time in a very long while, Runsu was victorious, but he must not have felt victorious, because when Verga met his gaze, beaten and gasping for breath beneath a Japanese fir, he turned, and he fled. Verga knew her daughter was waiting for her up in the mountains. But she couldn’t return. Not to China, and not to Shippai, not to Runsu. Once again, Verga was marching off into the wilderness, alone.

For the next fifteen years, Verga sought only the hard and tangible. She sought power. She sought anything that would keep her from powerlessness. She sought something clear and simple, and something that she was actually good at. And Verga was very good at amassing power. She let her martial arts skills go rusty as the benefits of her blue ki slowed with age, and instead spent her time scouring the corners of Asia for ancient ki techniques derived from old powers and terrible sorceries. She might occasionally participate in tournaments, a way of maintaining her fortune, but other than that Verga Ilgraven faded from the public scene. The thought of people, always somewhat uncomfortable to Verga, even at the best of times, was now downright frightening to her. Power had been her first love, and, she now realized, it should have been her only.

In the last few months, noting her loss in a recent tournament, Verga has decided to begin work again with her martial arts skills, and has quietly returned to the city in order to find sparring partners. She keeps on a straight face, deflects questions about her daughter, and hides admirably her great distaste for almost every single thing about the busy cities of Japan.

SPECIAL MOVES & TECHNIQUES ■ Singularity The world folds inward towards Verga, and a powerful gravitational pulse draws a single target towards her. The Singularity can move at ranges between twenty to a hundred feet, but cannot draw a target all the way towards her. Verga cannot perform any other kinds of ki-techniques while the Singularity is active, and, if it misses, it will take about twenty seconds for gravity to settle down enough to reuse the attack. Targets do not have their movements inhibited as they are drawn towards Verga. The reach of the Singularity appears as a multicolored rippling in the air, and, while extremely fast, it is possible to dodge.

Singularity is her only special move without a shot limit.

Another side effect of the Singularity is that it pins Verga in place while it’s active, allowing her to counter other, similar distance-grapples by using Singularity on another random target and locking herself in place. However, it also means she can't use Singularity while on the move.

■ Time Warp Verga uses both hands to swing a massive ax-headed blade of ki that folds time as it passes. Time Warp has medium range, but the spread of the attack is quite large—the blade itself is the size of a small car—and can travel about ten feet before dissipating. Targets hit by a Time Warp temporarily receive a small drop in speed, as their body’s passage through time is inhibited. Time Warp has three shots per hour, and is Verga's preferred attack.

■ Gravity Lens A powerful shielding move that warps incoming attacks around Verga, and exerts a violent outward push and downward weight on all nearby objects. It takes huge, ki-infused power to shatter the Lens, though its defense isn’t impenetrable. Gravity Lens has two shots per hour, though if shattered, becomes more difficult to use again too soon.

■ Aether Field A vicious scythe of light that moves at high speeds. With middling damage, the Aether Field is Verga’s weakest attack, but it has long range and moves extremely quickly—Verga’s most versatile move. She can grab onto the Field’s tail end and use it to close distances quickly. Aether Field has two shots per hour.

■ Paradox Verga phases her body through dimensions, allowing her to dash at extreme speeds by flickering through spacetime. Paradox has two shots per hour.

■ Supernova A luminous ki attack that spreads out from Verga as a thick, rippling wave of stardust and superheated energy. The Supernova has wide reach and spread, and can dizzy opponents with the strength of its light. Supernova has one shot per hour.

■ Black Hole Verga hurls a projectile of crackling gravity, then detonates it at will. When a Black Hole detonates, anything loose within ten feet is sucked towards it and dealt crushing gravity damage. Once they reach the center, the target immediately goes free. However, Verga is also affected by this attack, and has to time the Black Hole to ignite while she herself is out of range. If succesfull, it can interrupt combos and create an enormous hole in an enemy's tempo, opening them up to further attacks. Black Hole has one shot per hour.

■ Dark Matter A powerful, invisible attack that warps space and time as it moves. Dark Matter has medium range, high damage, and is exceptionally dangerous due to giving little physical warning before striking a target. Dark Matter is one of Verga's strongest attacks, and has one shot per day.

■ Antiparticle Igniting the atoms themselves, Verga unleashes a massive, highly destructive blast that overwhelms everything it touches with an oppressive cold heat. Antiparticle is Verga’s single strongest attack, bar none, but it is a short range move that requires Verga be within punching distance of her target. Antiparticle has one shot per five days.

SUPER MOVES ■ Harmonic Release A technique Verga developed using tai chi principals of balance and rhythm. Verga overrides the limits of her body, pushing her natural abilities right over the brink. Adrenaline and oxytocin production skyrocket, her heartbeat slows while each beat pounds like the world’s largest drum, and Verga gains a dramatic, supernomadic increase in movement speed, reaction time, and hit strength, as well as endurance to extreme temperatures. This is an entirely physical, martial technique, and does not rely on ki. However, it will only last for about five minutes, and once it wears off her speed and strength are halved for the immediate future.

Unlike her daughter’s Full Release, a move that forces the body into overdrive like a screaming taskmaster whipping an unwilling servant, Verga’s Harmonic Release seeks to breach human limitation through symphonic balance between mind and body, and, while exhausting, does not inflict as serious harm on the user as the Full Release.

WEAKNESSES & LIMITS While Verga’s ki attacks are enormously powerful, their raw power is also their greatest downside. Verga has pursued only the most dangerous of techniques during her quest for power, and, as a result, most of her special moves have a limited number of ‘shots’ before her body can no longer sustain them, and she must act conservatively against stronger foes, something that doesn’t come naturally to Verga due to her pride. In addition, almost none of her abilities can safely be used in closed in spaces, like hallways, and are difficult to use without harming allies. This also means she has a certain lack of versatility, as her abilities cannot be easily fine tuned or controlled—they operate at either 0%, or 100%, with no middle-ground.

If her abilities are spent, she has to rely on martial arts, and, while more than competent, her style focuses on self-defense, and isn’t appropriate for the shows of aggression and power that Verga relies on by nature.

Verga’s old fascination with fame has faded in the last twenty years, and she now has a very low opinion of it, and people who seek it out.