Federal Republic of China

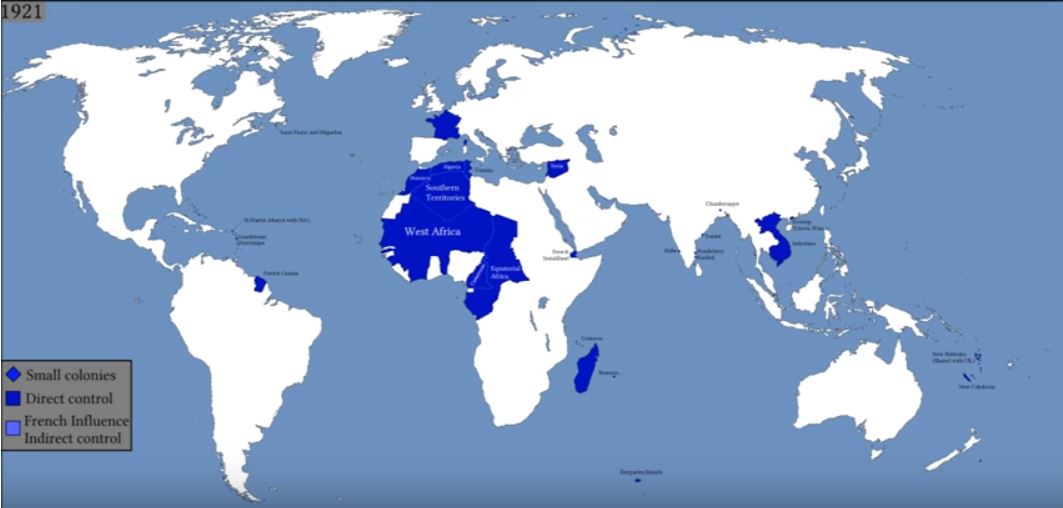

Map:

(blue)

The 1911 Xinhai Revolution would prove a momentous occasion in Chinese history as thousands of years of imperial history came to an end and the transition began into a modern Republic. In just over four months the once great Qing dynasty was toppled with the abdication of the Emperor Puyi. The fall of such an Empire marking not just a transition of China into a brand new era but the beginning of new troubles and the disintegration of China as its fringe territories such as Mongolia split free from the fractious and sudden bursting forth the blossom of a new historical chapter. As the sun set over the Qing, the rising star of the Chinese Republic took to the sky. But all was not clear, as clouds enveloped the nation.

The defeat of the Qing Empire left a nation to be reorganized by the fledgling Republic. For his services in negotiating the abdication of the child emperor Puyi, Yuan Shikai, the commander of the northern Beiyang Army was named the Provisional President of the Republic by the southern government, lead by Sun Yat-Sen. Though, while declared president as reward for his endeavors, the paranoid and militaristic Yuan Shikai was stubborn in leaving Beijing, the center of his Beiyang enforced power. Frustrated by the refusal, the southern government attempted to negotiate with Yuan Shikai to no avail. Rumors and stories of conspiracy to commit a coup only widened the gap. Yuan's response to the coup also weakened Sun Yet-Sen's and the southern government's bridge as Yuan purged his own officer corp in response and dug in his feet.

Moving quickly to assert his legitimacy as a governor, Yuan Shikai in early February 1912 hastily assembled a Republican government in defiance of the waiting Nanjing-based government. With his Beiyang Army led National Assembly he was named president with Cao Kun as his premier. Together the two sought to organize against the befuddled southern revolutionaries as well as to cement their own power. For their part, the Nanjing Tongmenghui government of the south sought to consolidate their position against theirs, Sun Yet-Sen and his vice president Huang Xing flitting between Shanghai, Japan, and Nanjing to organize their resources and their support. The young Tongmenghui government felt their grip weaken despite their efforts, as it was believed that many of the governors of the southern provinces supported Yuan Shikai and the Beiyang Republic. International support was tepid as well, with the nations of the world hesitant on supporting one government or the other as the legitimate representative of the Chinese state.

The difficult political climate made it so that Sun Yet-Sen had to act on and make concessions to the earlier positions of federalism proposed early in his revolutionary career. Subordinates like Chiang Kai-Shek were furious at the proposal, pointing to the dire situation that the movement now faced marching towards conflict between its two divided halves. Still, political forces moved on and Sun Yet-Sen made conditional arrangements for a federal republic in China pending the ending of current hostilities. At the time, November 1913 Chiang found himself humiliated and imprisoned in Shanghai when the British administration of the Shanghai International Settlement put charges against him for his associations with the settlement's Green Gang, sparking another crisis within the Republic.

The present discontent and mounting hostilities between the two republics also called for a change in the government. As the goal of overthrowing the Qing dynasty had been passed, satisfying more-or-less the conditions of the former then provisional government, the Nanjing government moved to reconstitute itself on a more permanent basis as the crisis between them and the Beiyang government continued, as the implications were becoming clear that legally they were subjects to the northern military republic. As China tensed, a movement within the government lead by Sun, Huang Xing, and Song Jiaoren saw to the beginning of the transformation of the southern Nanjing republic and of Sun's party itself.

Meanwhile, the international embarrassment of the arrest of Chiang threatened the quest for legitimacy Sun Yet-Sen was on as tensions mounted in the hazy and blurry frontiers between the Kuomintang and the Beiyang governments. But during negotiations with the British for Chiang's release fortune played a glowing hand as Yuan Shikai and his government moved to name him a new emperor for all China on August 15, 1915. In a swift and daring move, Yuan Shikai was named the Hongxian Emperor, and the Republic under him was abolished. However the move was ill-calculated and the business and political contracts with foreign powers he had cultivated melted away. Yuan's power had long been in decline since kowtowing to the Japanese and meeting their full demands for the extension of the privileges in northern China. These two punches dealt the deceleration did not comes with the support he had imagined. Much of China wavered and turned to reject him. The city of Beijing itself began to talk of the possibility of simply restoring the boy emperor Pu Yi and bring the Qing back to the light. The poorly calculated move was the push the south needed to grasp legitimacy tight in its hands.

As support moved south Yuan Shikai was forced into retreat as his legacy crumbled in front of him. He could not live long enough to salvage what he had built, and he died a hundred thirty four days after his announcement as emperor from uremia. The Beiyang government soon collapsed into a shadow of itself. Northern Republican reconvened the government in Beijing, but the tidal waves set in motion by Yuan's move towards power and his death were already washing across his northern military command and there was little they could do.

These waves though came onto the southern Republic like a refreshing rain and breathed back life into the movement. With Shikai's coronation and then death, Sun Yet-Sen and his allies could operate as a legitimate government themselves and quickly reconstituted their power before crisis struck. The Tongmenhui emerged not as itself anymore, but as the Nationalist-Kuomintang party, and the provisional government of the south as the Provisional Government of Southern China with the stated intent of bring back into the fold northern China and reforging the nation whole again. The second provisional government was declared and organized on September 25th, 1915 with Sun Yet-Sen re-elected as president. Song Jiaoren was elected premier. They immediately turned their attention to the Beiyang assembly.

In the northern assembly, politics were quickly taken back by supporters of Sun Yet-Sen and the southern Republican movement who acquired a majority of seats. At the same time, the British finally released Chiang Kai-Shek on the conditions he never enter Shanghai again, he retreated to Guangdong. Between the two Republics stood the massive crises of unification of the nation, and Europe's ongoing Great War and its repercussions in China.

The restoration of the Beiyang government and the ascendancy of his Kuomintang party within it meant that in a nominal sense Beijing was under the control of the new provisional government. Though the KMT Beiyang government had elected its own independent president, and the physical distance between them and Nanjing was made all the wider by Yuan's former officers forming warlord governments between them. None the less the two worked together as close as they could over the matter of the Great War. There was a movement among the Republic to cut their ties with the German Empire, though Sun Yet-Sen opposed this. All the same however millions of Chinese were leaving for Europe to serve as laborers in the European war and so there was a large expat interest in it. For assistance on the matter, and to help handle domestic issues Sun Yet-Sen tipped to the left in Kuomintang politics and favored the socialist contingent of the party when he sent a dispatch to the Second International in Paris for organizational assistance in early 1917. The later arrival of European socialist and communist organizers as well as political refugees from the failed revolution in Russia sparked a jump in southern political leanings as the integration of both contingents into the political cliques of China saw a left-ward shift in its operations.

Resolving the Republic's issue on the war, Sun Yet-Sen declared the official neutrality of China in December of 1916, though with predilections to the support of the central powers unofficially. The Northern Government however threw its full meager weight behind the allies to the annoyance of Sun. They committed even more Chinese to the allied lines in their organized labor battalions. The lukewarm position however of the southern Chinese Republic however saw to it that they were conditionally positioned to accept the task of taking on Europe's war production. As allied and central powers both demanded and sought out commercial allies to build and supply the war the Kuomintang government accepted the opportunity to receive what foreign development it could, even if temporary and for the next several years would build its industrial base to outfit the competing demands of either side, even as espionage and international violence broiled between the factories as international commissioners sought to shut down the other by rallying their work-forces against the other as traitors.

The arrival of Communists and socialists into the government gave Sun the operational opportunity to organize his social policy, and they their own in China. The KMT-left was able to institute Sun Yet-Sen's welfare programs and to rebuild the faltering tax base of southern China. As well, organizers who were several years prior organizing workers and peasants in Russia were again organizing workers in China. Especially as labor tensions mounted between workers of different firms as an effect of the war, new national labor unions were deemed appropriate to unify and consolidate China's workforce and to quell opportunistic violence between them and the firms they represent. Though Sun Yet-Sen asked they be state controlled unions, he was rebuked by the left and the invited organizers who worked to build independent unions.

Chiang Kai-Shek however, who had been rebuilding his political organization in Guangdong distrusted the growing unions however, and had been seeking out using the unrest caused by the foreign manufacturers to rise his political star over the rest of the Republic. But exiled from Shanghai and from his allies in the Green Gang there, and everything else eroded from his brief imprisonment he had only one thing: to bide his time. Using what little influence he had left however he did set to work. Founding the Whompoa Military Academy in 1920 he went about rebuilding his position with the military by attracting foreign military advisers to teach and organize a new officer corp for the Republic. He had dreams to and was promised the opportunity to retake the north who at this point were descending into continuously fractious warlord-ism as the Beiyang government itself weakened.

Attracting career officers and adventurers from Japan, America and the exiled Russian officers he organized his first generation of instructors at his academy. As he attracted students, he would often loan out his classes to the city of Guangdong in anti-riot operations when feuds between Allied and Central Power manufacturers broke out. These adventures helped to build his brand and bring him back into the Kuomintang on the right. However, his position even within his own academy was weak as the ex-communist officers managed to undercut his authority. A disparaging display of such to Chiang was when they petitioned to open classes on political agitation, or they would walk out. He was forced to bow to them, feeling bruised. His sense of being wronged only mounted and would inform his career to come.

In 1921 Sun Yet-Sen gave the order to Chiang Kai-Shek to pursue the campaign on the north and he set out from Guangdong with his army. He crossed several miles from Shanghai, which has marked the point at which the failed Beiyang state and the Kuomintang met. However: he did not enter it. Tensions within the Republic itself prevented himself from doing so, and organizers within the city had cleared it of Warlord influence anyhow. It is to this day a widely believed story that the people of the city were clued into some intention of Chiang Kai-Shek to flaunt his exile and enter into Shaghai and he would issue out some reprisal there against the British assembly. But for one reason or another, he showed restraint and kept moving, entering into warlord territory.

The fractious and broken political landscape meant that Chiang had little resistance in the north and he reached Beijing on July 18th, 1924. Incidentally, the following month Germany announced its cessation of its Pacific Island territories to China to flaunt the Japanese. The Japanese however did not seem to care, and claiming to have not been let known of the change occupied the islands and did not leave, sparking tension among the allied forces.

In January 1925 the other warlords were soundly defeated, however troubles loomed when the National Revolutionary Army arrived to Manchuria, to their surprise they found the Russians had seized and occupied much of the territories and refused to to surrender them to China. As well, their presence was threatening the Japanese lease territories and the Japanese made a new point of tension for the Allied coalition as they threatened war against Russia. For a brief period Sun Yet-Sen attempted to feverishly negotiate with the Czarist authorities in Manchuria to no effect. Worse yet: they considered any act of resistance by the native population as an act of aggression by China or Japan against them and tensions on the border worsened. An attack by the Russians against Chiang nearly drove his surprised army back to Beijing and Chiang declared it a war, Sun Yet-Sen however was far less insistent, but by this time he was succumbing to an un-named illness and was taking more and more time off from governance to rest. Chiang all the same pushed the Russian army back to where they had started and established a strict zone of military control to resist them.

By this time, the war in Europe had wound down into its unsettling peace and a long process of diplomatic negotiations were underway. On February 14th, 1925, Sun Yet-Sen made a voyage to Beijing to announce the unification of China, at least symbolically and to initiate the proceedings to move the government to the ancient capital. However he was too unwell to do anything besides issue a speech on his arrival. As soon as he left the microphone he was shuttled off to the hospital where an American surgeon diagnosed him with liver cancer at the age of fifty-eight. He was given ten days to live and he was treated with western medicine. Protests by the Republican government in the south were made to have him returned to Nanjing for traditional Chinese medicine but the hospital refused. Calls were made to Chiang to intervene and to bring Sun home, but he was occupied elsewhere on the line with the Russians and the message was lost. Sun Yet-Set lived for twenty-five days, well beyond the time he was given but incapable of doing much of anything and he passed away, leaving behind a will to the Republic. The Kuomintang went into a period of mourning for him and he was returned to Nanjing for his funeral. Already plans were underway to build him a tomb in the capital, but for everything real there were more pressing concerns for the government to worry about on the horizons.

To replace Sun Yet-Sen, his latest premier Zhang Renjie was named president of the Republic to fill out Sun's last two years in his second six-year term as president of their second Provisional Republic. The wealthy French-connected financier, and philosophical Anarchist had his work cut out for him. While a leftist, he was an avowed anti-Communist and quickly alienated the new Chinese Communist Party, which had spun off from the Kuomintang as political disagreements mounted between it and the less radical members of the nationalist party's center-left. But Renjie also alienated the right, having under Sun Yet-Sen been a source of consternation and vilification by China's landlord class for the building projects Sun allowed him to manage on behalf of the state. And while he worked closely with Chiang and the army many observed that it was perhaps a strained relationship. Renjie's domestic issues he adopted from Sun were also not helpful. With the winding down of the war in Europe war-time production off shored to China also waned and so were the irregular imports of silver and gold to pay for it. While European powers still owed substantial capital to China, the effect of the late war decline of production was felt in China in the form of steadily falling unemployment.

To help mitigate the looming disaster this turn would inevitably pose, Renjie worked with his fellow major Chinese financier T.V Soong.

Soong, a Chinese Christian and wealthy financier had managed to place himself as both the brother-in-law of the recently passed Sun Yat-Sen and current general Chiang Kai-Shek. Current finance minister under both Sun and Renjie he was a readily available source of assistance, and had known Renjie from the Shanghai stock exchange. He had studied business in America, and brought that American education and connections to China to help finance the revolution. Having once before constituted the finances of the early government, he answered the call to do so again as unemployment mounted.

The plan between the two of them was to simply refinance the debt owed to China abroad and sell it to investors back in Europe and to the Americas, or to put it up as collateral for loans. Doing so shored up the accounts in the short term, allowing the government to pay for the unemployment benefits to come. As well, they sought out how to maximize China's land-based Georgist tax system in the newly acquired northern provinces. During this time, several proposals for light tariffs were made to the legislature with minimal effect.

In addition, the proposal for an expedition similar to Chiang's northern campaign was proposed for the west, which through the intrigues of China's shifting politics over the passed decade had succumbed to a series of minor revolts against the local governments replacing several local Republican governments with new independent governments. The move it was hoped would help mitigate the rising unemployment through conscripting the recently unemployed and to refurbish the western owned factories for Chinese use. The proposal was also met weakly in the legislature, but at the same time this was occurring a strike wave hit China.

Responding to the growing unemployment the Chinese Communist Party organized vast groups of the unemployed into unemployment unions who sought to press greater social and political demands against the Republic of China. Among these were included an end to the institution of China's rural landlords, who in the time the Republic still acted as ancient noble land barons commanding their armies of serfs. They also demanded a further nationalization of industry and an income tax to help redistribute the wealth. The strikers also demanded the expansion of political suffrage and make the republic's political environment accessible to the greater mass of people. The strike wave proved so large in fact, that it spilled beyond the RoC's borders into Hong Kong where for months it froze the ports of the British colony and Hong Kong's economy ground to a halt and was held captive demanding increased pay and local autonomy for the colony.

Renjie's inability to respond to the sudden strike greatly damage his respect in the Republic and all further legislation he had put forward was frozen. Acting around him critics in the legislature and the other three branches of government moved to appoint a new premier, Guo Jin, a mild socialist and a mid-tier official to negotiate with the striking Communist Party.

Chiang Kai-Shek responded to the strike predictably and he turned his army around to head south to engage the strikers during negotiations. While his influence was weak, Renjie struggled to hold Chiang back before he could make the situation worse through mass slaughter. The CCP was sensitized to the situation and also operated with its friendly officers to stall the general and ceded to the demands of Guo Jin on a promise and dissolved the strike. Under the direction of Guo Jin, many of the disused western factories were forcefully nationalized and reopened to the protests of the European powers, who now had none of the strength left.

1927 came as a momentous moment in China and the world as simultaneously the war in Europe was drawn to an official close, even though broad and large scale hostilities had largely been over for the passed three years. As well, 1927 was an election year in China, and the National Assembly was reconvened to elect a new president. Zhang Renjie had no hope in the elections and withdrew his name from the running and retreated into private life. Guo Jin, always a second-rate bureaucrat disappeared back into government. The only serious contender came in Chiang Kai-Shek who rode on a wave of support for his deeds in the north. On the support of his victories in the Northern Expedition Chiang Kai-Shek was elected president, with TV Soong as his brother-premier. His political mission for the immediate future was clear: to push the Russians from Manchuria.

Before he could mobilize his forces however he needed to solidify his standing at home. The Communists enjoyed post-strike a substantial base of support among the urban cliques of China and for a time had harbored suspicions towards him. Fearing that they may rise in revolution against them he needed to occupy them. Going before the Legislative Yuan, Chiang began with reading the Will of Sun Yat-Sen, a tradition began by Renjie in ceremonial remembrance for the former president. The wall called for the restoration of national unity, the abolition of the unequal treaties, and to progress the Republic. Using the Will, he moved to re-propose a motion by Renjie to mount an expedition to the West. Outlining a basic strategic plan, he offered up a set of officers to lead the march: Zhou Enlai, Liu Siàu Tha̍t, and Zhu De.

Chiang's hope would be that in dispatching several communist officers to another front, and with minimal gearing that he would move them out of their reach of him. The three would coordinate and head westward quelling the unrest and expand China's territorial integrity, while Chiang's regular army would seek to mobilize against the Russians. The motion went through with success, and the armies were mobilized westward in October 1927.

As the Western Expedition mobilized, Chiang withdrew to chart his strategy for Manchuria. At this time the global wires were electric with news of the cessation of hostilities in Europe: peace at last. But an unsettled peace. With it came no changes or concessions that might mark one side or the other as the victor. Among the diplomatic community in Nanjing, the consensus was that of defeat for all the European powers. The occasion opened an opportunity for Chiang to poach several low to mid-ranking officers in Western and Eastern Europe, who without a war found themselves without a career to recruit for Whompoa.

As winter set in Chiang forestalled his planned invasion of Manchuria. During this time, Japan began to re-open hostilities in Manchuria and launched an attack from Dalian against Russian forces to clear their railways that had been choking their leased colony of the resources needed to make it economically viable. By spring the Japanese offensive was well underway and before the snows melted Chiang obtained legislative approval for war and the Chinese Republic declared war on Russia, or rather the Russian Far East. The political situation in the Russian Empire had deteriorated considerably since 1925 as the royal family began to lose the first of its support under the still simmering demands for reform. For the Russian's part admitting as such in private to the Chinese, the Russian ambassador confided in Chiang privately that he was marching against the Far East, and not Russia proper though other diplomatic forces protested the decision to go to war.

Chinese forces entered Liaoning province proper on March 3rd, 1928 and engaged Russian forces. By July Chinese forces met with Japanese forces and a tentative truce had to be drawn up by which either party swore to not engage the other and to push the front north. The war progressed slowly, complicated by the poor terrain until the Chinese and Japanese armies converged on Tongliao and the two armies laid the small city to siege. Russian relief forces arrived and managed to push the armies back.

Meanwhile in the west, the Western expedition went along better than Chiang could have expected. The expedition armies arrived at their staging ground of Chengdu and prepared to approach the Longmen Mountains, which marked the point at which Republican control was nascent at best. Operations began in November as scout planes were dispatched to identify any clear resistance within the mountains and before December came they moved across the range, entering the Tibetan Plateau as the snows were falling in December. Brief skirmishes prevailed over the winter with bandit armies but operational ability was hampered due to lack of equipment and the three commanders agreed to cease operations for the winter and to concentrate on preparing logistics to the Republic proper. As spring melted the snow the armies move on again and reached Yushu as Chiang was beginning his campaign against the Russians. The first real engagement with the Ma Clique armies began there.

The Western Expedition became known for its guerrilla style and improvisation. The conditions forced upon them by Chiang was meant to slow them down, but the trio of commanders found ways to work around them. Instead of engaging in formal organization a series of asymmetrical engagements were made. The political organization of the men as well served to pull the populace away from the Ma armies, and starting slow at first the expedition rapidly picked up speed, arriving in Xining in the north by July, at which point organization within the operation had come to a point where the commanders commissioned for the informal manufacture of their own arms and ammunition locally. The Expedition's momentum became such that within the year the Ma family was forced into retreat, and they disappeared from Qinghai, leaving the government to the commanders who quickly brought the region under organized military control as they ratted out the remnant of resistance.

Instead of pressing on the three marshals organized Qinghai further. Through Liu Siàu Tha̍t the local communities were organized as councils from which the local regional legislature was raised. But arguments between the marshals as to the political course sparked a rivalry between the three that endangered the campaign. The spark came to such a head, that dispatches to Nanjing irritated the central military command who broke the rivalry by ordering each of them on. Zhu De was ordered to re-mobilize for Mongolia, Zhou towards Tibet, and Liu on to Xinjiang.

Of the campaigners, Enlai's forces encountered stalwart defense from the Tibetans who blocked his army's advance onto the Tibetan Plateau. Undermanned and far from any support Enlai was forced to entrench his army and to wait out any attempt by the Tibetans for a counter-offensive. His offensive faltered here, and would not make any more progress for the rest of the offensive.

Zhu's campaign into Mongolia was ill-fated, while he was able to quell rebellion in the rest of Gansu his army could not progress beyond the Gobi desert despite his efforts. A small battle within Mongolia however was initiated when on February 4th, 1929 a motorized division from Zhu De's army engaged a Russian force that had come to occupy the territory in the intervening years. Zhu De's men were roundly defeated, and forced into a hasty retreat back into China where his men were able to repel the Russian and Mongolian counter-offensive. Recognizing the mission was lost, he chose to simply consolidate Gansu as he and his comrades had in Qinghai.

Further from home than the rest, Liu Siàu Tha̍t had more luck in Xinjiang than his comrades and made a hurried advance through the province scattering the rebel East Turkestani armies and aiding in the restoration of the Republican provisional government. He was capable of the same level of organization in the far western province, and had pacified the area by May 5th, 1930.

Chiang, expecting the failure of the expeditions had fallen under distress. The victories of the Three Marshals, both politically and militarily helped to embolden the Communist party and launch them further through the ranks of both party and state. While it is only confirmed he was privately despondent while publicly celebratory the Communist Party would come to allege he plotted to have the three assassinated. While answering a summons to return to Nanjing, the train of Zhu De would derail, killing the general. An incident in southern Gansu would injure Zhou Enlai in an explosion, which while not killing him crippled the man, and he was obliged to retire from the army. What was believed to be an attempted bombing of Liu would occur in Urumqi, but a stroke of fortune meant he was able to entirely miss the explosion when he answered a summons for tea with a local party official.

Chiang's fortunes in the east didn't change much for the better. While managing to press the Russians close to the border, Manchuria became effectively split in three ways. The independent forces of Japan, China, and Russia would converge on Harbin as they had met before. And while the front was not known for its lack of errors in the field, a particularly severe incident would be alleged outside Harbin.

Chinese aircraft patrolling the area during afternoon of April 1st, 1930 encountered an armed column moving south towards the Lalin river. Pinning it for a Russian column the aircraft engaged, blowing the bridge over the river, 64 miles from the city of Songyuan. The air wing would pass over the column and engage it. The column was a convoy escorting a Japanese officer from inspecting the Japanese forces outside of Harbin. Chiang's forces claimed they were not involved, and no such aircraft were in the area. But the incident was not taken lightly and the Japanese attacked Songyuan, dislodging the tired Chinese forces there and the following day bombers appeared over Beijing, accompanied by new confirming that the Japanese Empire declared war on the Republic of China.

The Japanese offensive over southern-western Manchuria would be fast, and by the end of the summer Chiang's army would be forced into a route. Incapable of properly supplying his troops because of the poor conditions of China's north following the Northern Expedition, the Republican Army was soundly beaten in every engagement. The Japanese forced the Republican army from Beijing on December 10th, 1930 and would reinstall Pu Yi – who had retreated to Japan as an exile – as puppet Emperor in China's north-east as a restored Qing Empire, which was little more than a faded shell behind the scenes, more in control of the Japanese than the Emperor himself.

By early autumn of 1931 the explosive progress of the Japanese pushed the Chinese army to the Yangtze river, where they held with their backs against the river. European tourists in Shanghai would remark in these days the flashes of Japanese bombs could be seen from the city along the northern horizon as The Bund was filled with tense military activity as Chiang's forces for the first time entered Shanghai. The local Communist leagues raised a militia to support the troops. By this time a air and naval war erupted over the Southern Chinese coast from Taiwan. But southern China, longer held by the Republic and more developed proved to be a more difficult front for the Japanese troops that could do little more than land or engage in bombing raids against the Chinese forces. Attempted landings would be made in Fuzhou (October 2nd, 1931), Quanzhou, Xiamen (November 8th, 1931), and even Hong Kong and Macau (January 10th, 1932) in hostile dismissal of European powers. And while the Chinese troops managed to dislodge the Japanese from Macau by March, the dense mountainous terrain of Hong Kong turned into a long siege as part of the larger Battle of Guangzhou which lost its land-war characteristic and transformed into an air war. Japanese soldiers would also retaliate bitterly against Hong Kong for several attempted armed uprisings against the occupiers who turned their occupation into sporadic episodes of street warfare.

With a large and even growing contingent of the Chinese army in the west, now uniformly commanded by Liu Siàu Tha̍t the Japanese thought to cut the Republican army in two and their Gansu offensive opened in August of 1932. General Liu was ordered to respond, and he routed the Japanese at Xi'an.

The Japanese offensive quickly found its breaking point at their defeat of Xi'an. Stretched thin over a large chunk of China they ran into difficulties in continuing their offensive. Further, operating far from the sea they ran into issues operating deep in the rugged Chinese interior whose mountains confounded Japanese offensives. They were forced into a defensive posture early in the winter of 1933 as the Republic of China faced a new election.

Appealing to the national crisis, Chiang demanded the support of the National Assembly, citing the current state of the war. And though the course of the crisis had damaged his base within the electoral Assembly, he was able to win the election. Chiang was able to also credit his victory to the new allies to the Chinese, the Germans who after the opening of hostilities with Japan began sending advisers to assist the Chinese in their strategy. The aid measures had only increased as it evolved from advisers to Germany's post-war surplus. German tanks and rifles became common among the Chinese lines. Through and after the election, Germany managed to receive Chiang's consent to study and experiment with German military theory in combined arms and German officers took the field directly. In the following year, TV Soong managed to renegotiate the German debt to China to zero with the offer to formally cede Qingdao back to China as soon as Chinese forces took the city.

Events in China at this time also attracted the interest of other foreign adventurers. Chiang's wife and sister to TV Soong, Soong Mei-Ling had managed to seek potential advisors and assistance from America early in the war through her husband's contacts with American business and academic circles. In 1932 her network of confidants an courted Americans had attracted the likes of Claire Lee Chennault, an American aviator who had served in the US Army's air signal corp, and who had taken his air training to Europe as a volunteer during the Great War. But due to America's non-involvement in the war had found himself an airman without much of a career in the force, while flying privately as a stunt pilot he was approached by Mei-Ling and was offered a commission to bring he and his company to China to inspect and train Chinese pilots. The offer would give Claire an escape from events to transpire soon in America.

As he landed in China his job began immediately. Having to travel north first through French Indochina to avoid the Japanese naval blockade he was quickly commandeered by Chinese officials before he could even settle to get to the job of reinforcing Nanjing, which being so close to the front was routinely threatened by Japanese forces. And while the Japanese did not yet have absolute air superiority, the Chinese air force was itself in disarray and in retreat. Through the remainder of 1932 he quickly re-organized and retrained Chinese pilots and went to the air to repel Japanese

aerial assault. Chennault's air core, named the Flying Tigers became the premier air force in the Central China theater, and as Japanese forces began to be pushed back in 1934 was credited with helping to preserve Nanjing as the government returned to the city.

The years of 1933-1936 came also as an adventuring boon to China, in part from the political purges in America during the period. The Republic of China, having long had deep contacts with America also meant that for many political refugees from the US, China became a natural place to retreat too, although the way there was often difficult from the war. Many who came to China to serve traveled From Australia to French Indochina and north into the Republic of China. But as they arrived the Chinese were quick to put them to use.

The war with Japan also afforded an opportunity for minor European officers who were without a career in Europe to leave to. And while the Germans maintained the most organized military and research partnership in China, many a French and British officer arrived to recast their depressed Great War careers as would-be heroes, gunslingers, and soldiers in China.

During the 1937 fighting period the Japanese made a push to try and close the gap by invading Southern China through Vietnam. Opening a new theater of operations the Japanese Empire invaded northern Vietnam and pushed deep into the country-side, taking advantage of staunch anti-French sentiment to also mobilize the Vietnamese people. Their independence would be short lived as the Japanese quickly set up a military government.

The closure of Vietnam also came with the full commitment of the Japanese navy that solidified its blockade on the country. While the Japanese could not mount a successful naval landing in the south, the constant naval bombardments and aerial war intensified the pressure and was able to reverse northern gains. The tightening of the Japanese noose at sea began in 1935 and by the same year Chinese forces were unable to progress. By 1937 the Chinese were in a slow retreat.

In 1938 the Russian Far East revived the Manchurian Front with a spring-time offensive in April against a lightly defended Japanese border at Heilongjiang. The moment could not come at a better time for Chiang who was staring down his third election. In time for the 1939 election he ceased on the momentum made by the Russians for the Chinese, and committing entirely to German strategy to try and at least retake the lost territories made a rapid advance north, actually outpacing initial offensive projections. The army was able to retake Beijing ahead of the election, and the act of it won Chiang re-election by a narrow margin. The Japanese thwarted the continued push north with a naval re-invasion at Shandong turning the Chinese forces around to enclose Japanese troops in the province. There was a renewed southern invasion when the Japanese mounted a landing under heavy air and sea support of Hainan, which they held and occupied until the end of the war. From Hainan the Japanese would attempt an offensive through Leizhou to take Guangdong. Japanese forces made it as far north as Maoming under intense naval support before being stopped.

In late 1939 and under economic distress Chiang needed a lifeline and in the current emergency situation he devised to invade Japanese Vietnam to liberate it from the Japanese. Assigning general Liu Siàu Tha̍t an emergency campaign was orchestrated with the French, who incapable of directly governing Vietnam would provide support for an invasion. Through former French colonial officers the Chinese linked up with Vietnamese agitator Nguyễn Sinh Cung to drive the Japanese from Vietnam and to re-open the country. At the same time, offended by Japan's hostility and occupation of Hong Kong the British through India opened a supply route through the rough and hazardous countryside of Burma's mountainous and feudal northern territories to link China with India. The work was hazardous and malaria plagued, but starting in 1937 had managed to open a dirt highway into China's Yunnan province in 1940.

With widespread guerrilla war on the part of Liu and Nguyen Japan was forced out of Vietnam by 1943. The new land connection via Burma helping to keep the Chinese state limping along even as Burma became threatened by the Japanese navy. The new injections into China re-energized what was feared to be an enervating state. The Japanese faced a new thorn as well when the Dutch closed the Malacca Straight to Japanese ships, ending Japanese operations in the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal. The Japanese would not press further in fear of losing its economic life-line.

The 1943 fighting season saw a Chinese army restored and re-equipped to take the fight to the enemy even as Japan continued to stubbornly shell the coast. Reigniting the northern front Chinese troops made another high-speed push northward making large gains in short time. Chinese troops arrived in Liaoning before the end of the year and sent the IJN in retreat to beyond the Yalu River; fearing a organized anti-Japanese insurgency among the Korean populace as in Vietnam the Japanese forces in Korea would remain to scrutinize and police the tense Korean population.

Still in advance, the Chinese moved to the Russians who had held the region in perpetual war with the Japanese since they relaunched their earlier invasion. But a weary and ill-equipped Russian Far Eastern Army was sent into an even more chaotic retreat before the Chinese who pushed far into the Russian Far East, overshooting their target.

Japan formally surrendered in 1944, and the Chinese obliged the Russian forces to surrender the Manchurian lands earlier taken by the Empire. At the independent conferences Japan ended its hostilities and transferred the mainland back to China, including treaty ports and ending its former leased colonial arrangements. Vietnam was transferred back to France under a tentative agreement with the local Vietnamese. The treaty was signed in Sydney on November 20th 1944. At roughly the same time, Japan was awarded Outer Manchuria, but denied Vladivostok which through diplomatic wranglings would become an independent city-state surrounded by China, although the city would send a representative to the Legislative Yuan and Chinese National Assembly as a commitment to represent the Russian population China now controlled, despite ironically not being in direct control of Vladivostok.

The celebrations in China were jubilant and grandiose. For the first time since the Xinhai Revolution the country was whole and the Republic held the dominant hand over the country. Through the remainder of the year and on into the next the intrigues of the Nanjing-based government was almost overlooked until the 1945 presidential election, where Chiang re-enrolled himself for another term. Word got out as well that Chiang was conspiring to use the newly victorious army to purge the Communists and the Socialists from power.

Obviously, the plot did not go over well when it broke and a contingent of the Chinese army showed up outside the recently reconstructed Executive Mansion in Nanjing lead by a young colonel named Hou Tsai Tang to prevent Chiang from issuing the order. Hou Tsai Tang, also known as Hou Tsai obligated the president-commander to withdraw from the running, and to allow the Chinese Republic to end the second provisional period that it had been in. Surrounded, and with his goose cooked Chiang was obligated to agree and defeated in his victory called upon the government to initiate the proceedings to come to the united Federal Republic of China.

Hou Tsai Tang for his efforts would astonishingly retire from military service after as proceedings commence. But a committed and card-carrying Communist, he was not distant from the constitutional convention to draft the new Republican government. The new constitution was announced on November 14th, 1945 and elections for an entirely new government were opened in January 1946. In May the first legislature, President and Premier and Executive Council, Control Yuan, Examination Yuan, and Supreme Court were assembled in Nanjing as the permanent seat of the new government. Under the new constitution the president would be elected to serve in five year terms, as would the posts in the legislature to elect two-thirds of the National Assembly and Legislative Yuan – respectively the Lower and Upper House in the new Bicameral structure – every five years, generally through direct participation but the provinces of China could also institute their own rules for election.

The first president to be elected post-war was Guang Su, a progressive socialist candidate from a more moderate labor tradition. His five year presidency was dominated by the reorganization and reconstruction of China's infrastructure particularly in the north. Guang Su's largest achievement being the passing of a pension for veterans of the war, though ability to pay the pension is made difficult by the poor record keeping of China because of the Republic's fitful and tortured beginning.

Guang Su was voted out of office in 1951 and a conservative Kuomintang officer would win the presidency. Li Su, a Sino-Japanese war hero would be slow on reforms and brought back from his post-Chiang retirement TV Soong to help in financial affairs. Much of Li Su's tenure would be marked by maintaining a status quo, as well as encouraging traditional standards in Chinese education despite Communist-led campaigning for modernization.

As Li Su faces election however in 1956, Chinese society the nation over looks ahead to a new evolution. Though the CCP has yet to win the presidency and has thus far played a secondary role, it has been no less active throughout the nation. Working among the factory unions and the peasants, the CCP is directly involved in organizing and educating the working and peasant class which cites continuing discontent with the landlord class that has survived the turbulent generation of China. And through the party culture of the CCP is Hou Tsai Tang, regarded as a hero in the left for stopping Chiang's plot to purge the Republic. Looking into the immediate future, it is believed the Communist Party as a very real chance of clutching the presidency.

The defeat of the Qing Empire left a nation to be reorganized by the fledgling Republic. For his services in negotiating the abdication of the child emperor Puyi, Yuan Shikai, the commander of the northern Beiyang Army was named the Provisional President of the Republic by the southern government, lead by Sun Yat-Sen. Though, while declared president as reward for his endeavors, the paranoid and militaristic Yuan Shikai was stubborn in leaving Beijing, the center of his Beiyang enforced power. Frustrated by the refusal, the southern government attempted to negotiate with Yuan Shikai to no avail. Rumors and stories of conspiracy to commit a coup only widened the gap. Yuan's response to the coup also weakened Sun Yet-Sen's and the southern government's bridge as Yuan purged his own officer corp in response and dug in his feet.

Moving quickly to assert his legitimacy as a governor, Yuan Shikai in early February 1912 hastily assembled a Republican government in defiance of the waiting Nanjing-based government. With his Beiyang Army led National Assembly he was named president with Cao Kun as his premier. Together the two sought to organize against the befuddled southern revolutionaries as well as to cement their own power. For their part, the Nanjing Tongmenghui government of the south sought to consolidate their position against theirs, Sun Yet-Sen and his vice president Huang Xing flitting between Shanghai, Japan, and Nanjing to organize their resources and their support. The young Tongmenghui government felt their grip weaken despite their efforts, as it was believed that many of the governors of the southern provinces supported Yuan Shikai and the Beiyang Republic. International support was tepid as well, with the nations of the world hesitant on supporting one government or the other as the legitimate representative of the Chinese state.

The difficult political climate made it so that Sun Yet-Sen had to act on and make concessions to the earlier positions of federalism proposed early in his revolutionary career. Subordinates like Chiang Kai-Shek were furious at the proposal, pointing to the dire situation that the movement now faced marching towards conflict between its two divided halves. Still, political forces moved on and Sun Yet-Sen made conditional arrangements for a federal republic in China pending the ending of current hostilities. At the time, November 1913 Chiang found himself humiliated and imprisoned in Shanghai when the British administration of the Shanghai International Settlement put charges against him for his associations with the settlement's Green Gang, sparking another crisis within the Republic.

The present discontent and mounting hostilities between the two republics also called for a change in the government. As the goal of overthrowing the Qing dynasty had been passed, satisfying more-or-less the conditions of the former then provisional government, the Nanjing government moved to reconstitute itself on a more permanent basis as the crisis between them and the Beiyang government continued, as the implications were becoming clear that legally they were subjects to the northern military republic. As China tensed, a movement within the government lead by Sun, Huang Xing, and Song Jiaoren saw to the beginning of the transformation of the southern Nanjing republic and of Sun's party itself.

Meanwhile, the international embarrassment of the arrest of Chiang threatened the quest for legitimacy Sun Yet-Sen was on as tensions mounted in the hazy and blurry frontiers between the Kuomintang and the Beiyang governments. But during negotiations with the British for Chiang's release fortune played a glowing hand as Yuan Shikai and his government moved to name him a new emperor for all China on August 15, 1915. In a swift and daring move, Yuan Shikai was named the Hongxian Emperor, and the Republic under him was abolished. However the move was ill-calculated and the business and political contracts with foreign powers he had cultivated melted away. Yuan's power had long been in decline since kowtowing to the Japanese and meeting their full demands for the extension of the privileges in northern China. These two punches dealt the deceleration did not comes with the support he had imagined. Much of China wavered and turned to reject him. The city of Beijing itself began to talk of the possibility of simply restoring the boy emperor Pu Yi and bring the Qing back to the light. The poorly calculated move was the push the south needed to grasp legitimacy tight in its hands.

As support moved south Yuan Shikai was forced into retreat as his legacy crumbled in front of him. He could not live long enough to salvage what he had built, and he died a hundred thirty four days after his announcement as emperor from uremia. The Beiyang government soon collapsed into a shadow of itself. Northern Republican reconvened the government in Beijing, but the tidal waves set in motion by Yuan's move towards power and his death were already washing across his northern military command and there was little they could do.

These waves though came onto the southern Republic like a refreshing rain and breathed back life into the movement. With Shikai's coronation and then death, Sun Yet-Sen and his allies could operate as a legitimate government themselves and quickly reconstituted their power before crisis struck. The Tongmenhui emerged not as itself anymore, but as the Nationalist-Kuomintang party, and the provisional government of the south as the Provisional Government of Southern China with the stated intent of bring back into the fold northern China and reforging the nation whole again. The second provisional government was declared and organized on September 25th, 1915 with Sun Yet-Sen re-elected as president. Song Jiaoren was elected premier. They immediately turned their attention to the Beiyang assembly.

In the northern assembly, politics were quickly taken back by supporters of Sun Yet-Sen and the southern Republican movement who acquired a majority of seats. At the same time, the British finally released Chiang Kai-Shek on the conditions he never enter Shanghai again, he retreated to Guangdong. Between the two Republics stood the massive crises of unification of the nation, and Europe's ongoing Great War and its repercussions in China.

The restoration of the Beiyang government and the ascendancy of his Kuomintang party within it meant that in a nominal sense Beijing was under the control of the new provisional government. Though the KMT Beiyang government had elected its own independent president, and the physical distance between them and Nanjing was made all the wider by Yuan's former officers forming warlord governments between them. None the less the two worked together as close as they could over the matter of the Great War. There was a movement among the Republic to cut their ties with the German Empire, though Sun Yet-Sen opposed this. All the same however millions of Chinese were leaving for Europe to serve as laborers in the European war and so there was a large expat interest in it. For assistance on the matter, and to help handle domestic issues Sun Yet-Sen tipped to the left in Kuomintang politics and favored the socialist contingent of the party when he sent a dispatch to the Second International in Paris for organizational assistance in early 1917. The later arrival of European socialist and communist organizers as well as political refugees from the failed revolution in Russia sparked a jump in southern political leanings as the integration of both contingents into the political cliques of China saw a left-ward shift in its operations.

Resolving the Republic's issue on the war, Sun Yet-Sen declared the official neutrality of China in December of 1916, though with predilections to the support of the central powers unofficially. The Northern Government however threw its full meager weight behind the allies to the annoyance of Sun. They committed even more Chinese to the allied lines in their organized labor battalions. The lukewarm position however of the southern Chinese Republic however saw to it that they were conditionally positioned to accept the task of taking on Europe's war production. As allied and central powers both demanded and sought out commercial allies to build and supply the war the Kuomintang government accepted the opportunity to receive what foreign development it could, even if temporary and for the next several years would build its industrial base to outfit the competing demands of either side, even as espionage and international violence broiled between the factories as international commissioners sought to shut down the other by rallying their work-forces against the other as traitors.

The arrival of Communists and socialists into the government gave Sun the operational opportunity to organize his social policy, and they their own in China. The KMT-left was able to institute Sun Yet-Sen's welfare programs and to rebuild the faltering tax base of southern China. As well, organizers who were several years prior organizing workers and peasants in Russia were again organizing workers in China. Especially as labor tensions mounted between workers of different firms as an effect of the war, new national labor unions were deemed appropriate to unify and consolidate China's workforce and to quell opportunistic violence between them and the firms they represent. Though Sun Yet-Sen asked they be state controlled unions, he was rebuked by the left and the invited organizers who worked to build independent unions.

Chiang Kai-Shek however, who had been rebuilding his political organization in Guangdong distrusted the growing unions however, and had been seeking out using the unrest caused by the foreign manufacturers to rise his political star over the rest of the Republic. But exiled from Shanghai and from his allies in the Green Gang there, and everything else eroded from his brief imprisonment he had only one thing: to bide his time. Using what little influence he had left however he did set to work. Founding the Whompoa Military Academy in 1920 he went about rebuilding his position with the military by attracting foreign military advisers to teach and organize a new officer corp for the Republic. He had dreams to and was promised the opportunity to retake the north who at this point were descending into continuously fractious warlord-ism as the Beiyang government itself weakened.

Attracting career officers and adventurers from Japan, America and the exiled Russian officers he organized his first generation of instructors at his academy. As he attracted students, he would often loan out his classes to the city of Guangdong in anti-riot operations when feuds between Allied and Central Power manufacturers broke out. These adventures helped to build his brand and bring him back into the Kuomintang on the right. However, his position even within his own academy was weak as the ex-communist officers managed to undercut his authority. A disparaging display of such to Chiang was when they petitioned to open classes on political agitation, or they would walk out. He was forced to bow to them, feeling bruised. His sense of being wronged only mounted and would inform his career to come.

In 1921 Sun Yet-Sen gave the order to Chiang Kai-Shek to pursue the campaign on the north and he set out from Guangdong with his army. He crossed several miles from Shanghai, which has marked the point at which the failed Beiyang state and the Kuomintang met. However: he did not enter it. Tensions within the Republic itself prevented himself from doing so, and organizers within the city had cleared it of Warlord influence anyhow. It is to this day a widely believed story that the people of the city were clued into some intention of Chiang Kai-Shek to flaunt his exile and enter into Shaghai and he would issue out some reprisal there against the British assembly. But for one reason or another, he showed restraint and kept moving, entering into warlord territory.

The fractious and broken political landscape meant that Chiang had little resistance in the north and he reached Beijing on July 18th, 1924. Incidentally, the following month Germany announced its cessation of its Pacific Island territories to China to flaunt the Japanese. The Japanese however did not seem to care, and claiming to have not been let known of the change occupied the islands and did not leave, sparking tension among the allied forces.

In January 1925 the other warlords were soundly defeated, however troubles loomed when the National Revolutionary Army arrived to Manchuria, to their surprise they found the Russians had seized and occupied much of the territories and refused to to surrender them to China. As well, their presence was threatening the Japanese lease territories and the Japanese made a new point of tension for the Allied coalition as they threatened war against Russia. For a brief period Sun Yet-Sen attempted to feverishly negotiate with the Czarist authorities in Manchuria to no effect. Worse yet: they considered any act of resistance by the native population as an act of aggression by China or Japan against them and tensions on the border worsened. An attack by the Russians against Chiang nearly drove his surprised army back to Beijing and Chiang declared it a war, Sun Yet-Sen however was far less insistent, but by this time he was succumbing to an un-named illness and was taking more and more time off from governance to rest. Chiang all the same pushed the Russian army back to where they had started and established a strict zone of military control to resist them.

By this time, the war in Europe had wound down into its unsettling peace and a long process of diplomatic negotiations were underway. On February 14th, 1925, Sun Yet-Sen made a voyage to Beijing to announce the unification of China, at least symbolically and to initiate the proceedings to move the government to the ancient capital. However he was too unwell to do anything besides issue a speech on his arrival. As soon as he left the microphone he was shuttled off to the hospital where an American surgeon diagnosed him with liver cancer at the age of fifty-eight. He was given ten days to live and he was treated with western medicine. Protests by the Republican government in the south were made to have him returned to Nanjing for traditional Chinese medicine but the hospital refused. Calls were made to Chiang to intervene and to bring Sun home, but he was occupied elsewhere on the line with the Russians and the message was lost. Sun Yet-Set lived for twenty-five days, well beyond the time he was given but incapable of doing much of anything and he passed away, leaving behind a will to the Republic. The Kuomintang went into a period of mourning for him and he was returned to Nanjing for his funeral. Already plans were underway to build him a tomb in the capital, but for everything real there were more pressing concerns for the government to worry about on the horizons.

To replace Sun Yet-Sen, his latest premier Zhang Renjie was named president of the Republic to fill out Sun's last two years in his second six-year term as president of their second Provisional Republic. The wealthy French-connected financier, and philosophical Anarchist had his work cut out for him. While a leftist, he was an avowed anti-Communist and quickly alienated the new Chinese Communist Party, which had spun off from the Kuomintang as political disagreements mounted between it and the less radical members of the nationalist party's center-left. But Renjie also alienated the right, having under Sun Yet-Sen been a source of consternation and vilification by China's landlord class for the building projects Sun allowed him to manage on behalf of the state. And while he worked closely with Chiang and the army many observed that it was perhaps a strained relationship. Renjie's domestic issues he adopted from Sun were also not helpful. With the winding down of the war in Europe war-time production off shored to China also waned and so were the irregular imports of silver and gold to pay for it. While European powers still owed substantial capital to China, the effect of the late war decline of production was felt in China in the form of steadily falling unemployment.

To help mitigate the looming disaster this turn would inevitably pose, Renjie worked with his fellow major Chinese financier T.V Soong.

Soong, a Chinese Christian and wealthy financier had managed to place himself as both the brother-in-law of the recently passed Sun Yat-Sen and current general Chiang Kai-Shek. Current finance minister under both Sun and Renjie he was a readily available source of assistance, and had known Renjie from the Shanghai stock exchange. He had studied business in America, and brought that American education and connections to China to help finance the revolution. Having once before constituted the finances of the early government, he answered the call to do so again as unemployment mounted.

The plan between the two of them was to simply refinance the debt owed to China abroad and sell it to investors back in Europe and to the Americas, or to put it up as collateral for loans. Doing so shored up the accounts in the short term, allowing the government to pay for the unemployment benefits to come. As well, they sought out how to maximize China's land-based Georgist tax system in the newly acquired northern provinces. During this time, several proposals for light tariffs were made to the legislature with minimal effect.

In addition, the proposal for an expedition similar to Chiang's northern campaign was proposed for the west, which through the intrigues of China's shifting politics over the passed decade had succumbed to a series of minor revolts against the local governments replacing several local Republican governments with new independent governments. The move it was hoped would help mitigate the rising unemployment through conscripting the recently unemployed and to refurbish the western owned factories for Chinese use. The proposal was also met weakly in the legislature, but at the same time this was occurring a strike wave hit China.

Responding to the growing unemployment the Chinese Communist Party organized vast groups of the unemployed into unemployment unions who sought to press greater social and political demands against the Republic of China. Among these were included an end to the institution of China's rural landlords, who in the time the Republic still acted as ancient noble land barons commanding their armies of serfs. They also demanded a further nationalization of industry and an income tax to help redistribute the wealth. The strikers also demanded the expansion of political suffrage and make the republic's political environment accessible to the greater mass of people. The strike wave proved so large in fact, that it spilled beyond the RoC's borders into Hong Kong where for months it froze the ports of the British colony and Hong Kong's economy ground to a halt and was held captive demanding increased pay and local autonomy for the colony.

Renjie's inability to respond to the sudden strike greatly damage his respect in the Republic and all further legislation he had put forward was frozen. Acting around him critics in the legislature and the other three branches of government moved to appoint a new premier, Guo Jin, a mild socialist and a mid-tier official to negotiate with the striking Communist Party.

Chiang Kai-Shek responded to the strike predictably and he turned his army around to head south to engage the strikers during negotiations. While his influence was weak, Renjie struggled to hold Chiang back before he could make the situation worse through mass slaughter. The CCP was sensitized to the situation and also operated with its friendly officers to stall the general and ceded to the demands of Guo Jin on a promise and dissolved the strike. Under the direction of Guo Jin, many of the disused western factories were forcefully nationalized and reopened to the protests of the European powers, who now had none of the strength left.

1927 came as a momentous moment in China and the world as simultaneously the war in Europe was drawn to an official close, even though broad and large scale hostilities had largely been over for the passed three years. As well, 1927 was an election year in China, and the National Assembly was reconvened to elect a new president. Zhang Renjie had no hope in the elections and withdrew his name from the running and retreated into private life. Guo Jin, always a second-rate bureaucrat disappeared back into government. The only serious contender came in Chiang Kai-Shek who rode on a wave of support for his deeds in the north. On the support of his victories in the Northern Expedition Chiang Kai-Shek was elected president, with TV Soong as his brother-premier. His political mission for the immediate future was clear: to push the Russians from Manchuria.

Before he could mobilize his forces however he needed to solidify his standing at home. The Communists enjoyed post-strike a substantial base of support among the urban cliques of China and for a time had harbored suspicions towards him. Fearing that they may rise in revolution against them he needed to occupy them. Going before the Legislative Yuan, Chiang began with reading the Will of Sun Yat-Sen, a tradition began by Renjie in ceremonial remembrance for the former president. The wall called for the restoration of national unity, the abolition of the unequal treaties, and to progress the Republic. Using the Will, he moved to re-propose a motion by Renjie to mount an expedition to the West. Outlining a basic strategic plan, he offered up a set of officers to lead the march: Zhou Enlai, Liu Siàu Tha̍t, and Zhu De.

Chiang's hope would be that in dispatching several communist officers to another front, and with minimal gearing that he would move them out of their reach of him. The three would coordinate and head westward quelling the unrest and expand China's territorial integrity, while Chiang's regular army would seek to mobilize against the Russians. The motion went through with success, and the armies were mobilized westward in October 1927.

As the Western Expedition mobilized, Chiang withdrew to chart his strategy for Manchuria. At this time the global wires were electric with news of the cessation of hostilities in Europe: peace at last. But an unsettled peace. With it came no changes or concessions that might mark one side or the other as the victor. Among the diplomatic community in Nanjing, the consensus was that of defeat for all the European powers. The occasion opened an opportunity for Chiang to poach several low to mid-ranking officers in Western and Eastern Europe, who without a war found themselves without a career to recruit for Whompoa.

As winter set in Chiang forestalled his planned invasion of Manchuria. During this time, Japan began to re-open hostilities in Manchuria and launched an attack from Dalian against Russian forces to clear their railways that had been choking their leased colony of the resources needed to make it economically viable. By spring the Japanese offensive was well underway and before the snows melted Chiang obtained legislative approval for war and the Chinese Republic declared war on Russia, or rather the Russian Far East. The political situation in the Russian Empire had deteriorated considerably since 1925 as the royal family began to lose the first of its support under the still simmering demands for reform. For the Russian's part admitting as such in private to the Chinese, the Russian ambassador confided in Chiang privately that he was marching against the Far East, and not Russia proper though other diplomatic forces protested the decision to go to war.

Chinese forces entered Liaoning province proper on March 3rd, 1928 and engaged Russian forces. By July Chinese forces met with Japanese forces and a tentative truce had to be drawn up by which either party swore to not engage the other and to push the front north. The war progressed slowly, complicated by the poor terrain until the Chinese and Japanese armies converged on Tongliao and the two armies laid the small city to siege. Russian relief forces arrived and managed to push the armies back.

Meanwhile in the west, the Western expedition went along better than Chiang could have expected. The expedition armies arrived at their staging ground of Chengdu and prepared to approach the Longmen Mountains, which marked the point at which Republican control was nascent at best. Operations began in November as scout planes were dispatched to identify any clear resistance within the mountains and before December came they moved across the range, entering the Tibetan Plateau as the snows were falling in December. Brief skirmishes prevailed over the winter with bandit armies but operational ability was hampered due to lack of equipment and the three commanders agreed to cease operations for the winter and to concentrate on preparing logistics to the Republic proper. As spring melted the snow the armies move on again and reached Yushu as Chiang was beginning his campaign against the Russians. The first real engagement with the Ma Clique armies began there.

The Western Expedition became known for its guerrilla style and improvisation. The conditions forced upon them by Chiang was meant to slow them down, but the trio of commanders found ways to work around them. Instead of engaging in formal organization a series of asymmetrical engagements were made. The political organization of the men as well served to pull the populace away from the Ma armies, and starting slow at first the expedition rapidly picked up speed, arriving in Xining in the north by July, at which point organization within the operation had come to a point where the commanders commissioned for the informal manufacture of their own arms and ammunition locally. The Expedition's momentum became such that within the year the Ma family was forced into retreat, and they disappeared from Qinghai, leaving the government to the commanders who quickly brought the region under organized military control as they ratted out the remnant of resistance.

Instead of pressing on the three marshals organized Qinghai further. Through Liu Siàu Tha̍t the local communities were organized as councils from which the local regional legislature was raised. But arguments between the marshals as to the political course sparked a rivalry between the three that endangered the campaign. The spark came to such a head, that dispatches to Nanjing irritated the central military command who broke the rivalry by ordering each of them on. Zhu De was ordered to re-mobilize for Mongolia, Zhou towards Tibet, and Liu on to Xinjiang.

Of the campaigners, Enlai's forces encountered stalwart defense from the Tibetans who blocked his army's advance onto the Tibetan Plateau. Undermanned and far from any support Enlai was forced to entrench his army and to wait out any attempt by the Tibetans for a counter-offensive. His offensive faltered here, and would not make any more progress for the rest of the offensive.

Zhu's campaign into Mongolia was ill-fated, while he was able to quell rebellion in the rest of Gansu his army could not progress beyond the Gobi desert despite his efforts. A small battle within Mongolia however was initiated when on February 4th, 1929 a motorized division from Zhu De's army engaged a Russian force that had come to occupy the territory in the intervening years. Zhu De's men were roundly defeated, and forced into a hasty retreat back into China where his men were able to repel the Russian and Mongolian counter-offensive. Recognizing the mission was lost, he chose to simply consolidate Gansu as he and his comrades had in Qinghai.

Further from home than the rest, Liu Siàu Tha̍t had more luck in Xinjiang than his comrades and made a hurried advance through the province scattering the rebel East Turkestani armies and aiding in the restoration of the Republican provisional government. He was capable of the same level of organization in the far western province, and had pacified the area by May 5th, 1930.

Chiang, expecting the failure of the expeditions had fallen under distress. The victories of the Three Marshals, both politically and militarily helped to embolden the Communist party and launch them further through the ranks of both party and state. While it is only confirmed he was privately despondent while publicly celebratory the Communist Party would come to allege he plotted to have the three assassinated. While answering a summons to return to Nanjing, the train of Zhu De would derail, killing the general. An incident in southern Gansu would injure Zhou Enlai in an explosion, which while not killing him crippled the man, and he was obliged to retire from the army. What was believed to be an attempted bombing of Liu would occur in Urumqi, but a stroke of fortune meant he was able to entirely miss the explosion when he answered a summons for tea with a local party official.

Chiang's fortunes in the east didn't change much for the better. While managing to press the Russians close to the border, Manchuria became effectively split in three ways. The independent forces of Japan, China, and Russia would converge on Harbin as they had met before. And while the front was not known for its lack of errors in the field, a particularly severe incident would be alleged outside Harbin.

Chinese aircraft patrolling the area during afternoon of April 1st, 1930 encountered an armed column moving south towards the Lalin river. Pinning it for a Russian column the aircraft engaged, blowing the bridge over the river, 64 miles from the city of Songyuan. The air wing would pass over the column and engage it. The column was a convoy escorting a Japanese officer from inspecting the Japanese forces outside of Harbin. Chiang's forces claimed they were not involved, and no such aircraft were in the area. But the incident was not taken lightly and the Japanese attacked Songyuan, dislodging the tired Chinese forces there and the following day bombers appeared over Beijing, accompanied by new confirming that the Japanese Empire declared war on the Republic of China.

The Japanese offensive over southern-western Manchuria would be fast, and by the end of the summer Chiang's army would be forced into a route. Incapable of properly supplying his troops because of the poor conditions of China's north following the Northern Expedition, the Republican Army was soundly beaten in every engagement. The Japanese forced the Republican army from Beijing on December 10th, 1930 and would reinstall Pu Yi – who had retreated to Japan as an exile – as puppet Emperor in China's north-east as a restored Qing Empire, which was little more than a faded shell behind the scenes, more in control of the Japanese than the Emperor himself.

By early autumn of 1931 the explosive progress of the Japanese pushed the Chinese army to the Yangtze river, where they held with their backs against the river. European tourists in Shanghai would remark in these days the flashes of Japanese bombs could be seen from the city along the northern horizon as The Bund was filled with tense military activity as Chiang's forces for the first time entered Shanghai. The local Communist leagues raised a militia to support the troops. By this time a air and naval war erupted over the Southern Chinese coast from Taiwan. But southern China, longer held by the Republic and more developed proved to be a more difficult front for the Japanese troops that could do little more than land or engage in bombing raids against the Chinese forces. Attempted landings would be made in Fuzhou (October 2nd, 1931), Quanzhou, Xiamen (November 8th, 1931), and even Hong Kong and Macau (January 10th, 1932) in hostile dismissal of European powers. And while the Chinese troops managed to dislodge the Japanese from Macau by March, the dense mountainous terrain of Hong Kong turned into a long siege as part of the larger Battle of Guangzhou which lost its land-war characteristic and transformed into an air war. Japanese soldiers would also retaliate bitterly against Hong Kong for several attempted armed uprisings against the occupiers who turned their occupation into sporadic episodes of street warfare.