Year 4605 L.R. (Lunar Reckoning), 3rd Pau

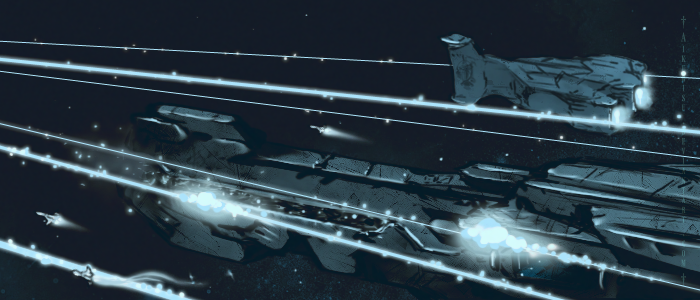

Above the ocean-moon of HuyOne-hundred and forty years ago“Hetman! A sleeper!” The ship before them rotated to aft in an endeavor to evade the enfilade from the AP Screamer, but to no avail. A molten paroxysm, a brilliant eruption of light, beautiful in its silence, and it was gone, scattered into a thousand-thousand motes of debris, briefly blinding the stars. Fusion-weapon streamers and coral-pink coil-light streaked and ignited far afield, radiant with thermonuclear luminescence; the line was holding (or so it seemed), their impulse-fields maintained. How had a sleeper been able to penetrate the vanguard?

“Hetman!”

The Screamer released another fullisade, instantly obliterating two of the escort fighters, while the rest of the detail struggled to react. The carrier riposted with their own barrage, but the Screamer deftly turned aside, having anticipated their weapons’ latency; theirs was no ship fit for true combat, and certainly not against the enemy’s spy-ships.

“They’re going to ram us, Hetman!”

“Divert energy to the bow aegis!”

“Where is Hetman So!?”

The rest of the escorts had likewise been destroyed in mere moments, leaving cool spasms of light and dross. The carrier fired once again, but the Screamer danced delicately around the streams.

“The bow aegis is at full power!”

“Brace for impact!

Brace!”

The sleeper, however, had other ideas, another target in its sights.

A wave of terror swept over the carrier.

“They know.”

The ship was convulsed as the Screamer rammed itself into its leeward side. In an instant, panels flamed, warning of a hull breech in the two lowest decks. Space sucked the atmosphere from the sixth cargo hold, dragging Mur-Po warriors in its wake, grasping blindly for purchase in the void.

Ghiza Inat, one of their unlucky number, her drawn faced dappled with blood, smirked grimly as her life slowly ebbed, the stars flooding her vision like small lightnings.

They had missed.

The thrall Sawala was blind. Yet he felt, somehow, that he was being led into the bowels of some conspiracy.

They had, for added precaution, extinguished his hearing and bound his five arms—he had lost the sixth during his capture—but he still sensed through the faintest of vibrations an argument occurring between a group of seven people. That sense, of vibration, of echoes, he had cultivated since his birth. He did not know why they had left a blind infant alive—perhaps because he had been born, a rare case in these days, of a union between the male and female sexes. He himself would not have been so clement, had he been in the position to choose. But he had ensured that none regretted the decision.

He had been imbued with the tenets of righteous combat by the School of Move-Like-This. In hands-to-hands melee, few proved his equal. And, having demonstrated his mettle, he was given the recourse to augment himself in order to provide the barest suggestion of vision—interesting, was it not, that they had not even cured blindness, whereas in other societies it was a long-elapsed specter of history? Even so, equipped with such trappings he had been able to fight, to lay down his life for the Notables and the Eightfold General.

But that was over now. Sawala had failed, long ago. Enthralled by their enemies. Blinded once more. Enfettered and impressed with the thought-tattoo of holy slavery. Oftentimes, he had lain awake, wondering for what purpose he had been spared his life. Of what utility was a blind slave, sans one arm? The slave armies of the so-called Ascendancy had achieved renown for their ferocity and prowess; and yet he had not been impressed into their service. Why then, was he alive?

“Slave.”

In a moment a vast voice overflew his senses. Had his hearing had been restored?

“I

know what you are.”

Sawala felt miniscule as the smallest particle of snow or the merest grain of salt. Drawn into a pinhead. The walls of his mind collapsed into themselves. His cells erupted into chain lightnings of phosphorescent sensation; his very flesh was permeable to the passage of unfettered thought. Atoms collided and specters danced behind his eyelids.

He discovered that in this flux, this no-space of porous thought, he too could brush his mind against other minds.

He, feebly indignant, probed back.

“What is this?”

The voice cusped him like water; he had to try very hard to gather all of his self up with it.

“

I AM YOUR LORD YOUR MASTER YOUR NUMEN YOUR KING.”

Sawala’s mind had been very nearly cloven; he grasped helplessly, freefalling through epochs of nothingness. Perhaps the voice suspected this.

How could it be in an instant so forceful yet so soft?

“I will show you what to do. You need only to listen.”

The voice left him. Sensation replenished his spangled limbs, perhaps too quickly; he staggered and collapsed to his knees, nearly falling upon his face without the support of his arms.

He felt rough hands collect him and jerk him back to his feet.

His hearing was returned to him once more, but it was different than before.

“Slave!”

A woman’s voice, clarion and rich, ricocheting between the walls of a vast chamber.

“It is no matter, Sap-Fa,” another voice, this time a man’s, rocky yet reed-like, snapped.

“Did you not sense it too, Oram-Di? He is an esper.”

“You did not realize, Sap-Fa?” Sawala felt a shifting of weight, two small booted steps, a large presence at his side.

“For this he was elected. Esperdom is requisite of this…

gambit .” The voice was cool, yet somewhat sangfroid.

Indignance.

“You were not required to know.”

“And with whom was he parleying? Insurgents? Or perhaps with the enemy themselves?”

Oram-Di chuckled wryly, turned a step more.

“Pray, do not probe, Sap-Fa. Were it for you to know, you would have already. Perform your duties, and

be silent.”

In a more sober tone, he added, “Not much time is left us.”

Sawala could only imagine the dimensions of this chamber; he had been transferred from Hetman So’s frigate, by way of high velocity clipper, dodging enemy fire as they went. How far had they broken into the line?

Another voice, deeper even than Oram-Di’s, echoed now, cold and undulant.

“Then the hour has arrived. Let us begin.”

Sawala sensed four more steps, and a vast being before him. The ship’s own respiration, of thrumming engine and metal, practically shouted out at him; far away, a muffled alarm tone sounded.

“Slave Sawala. Despite your genetic infirmity, you were known as a warrior of some acclaim before you were stooped to thralldom. We are

Mujad, and recognize your valor.”

Someone unclasped his fetters. The clang roared through the tremendous hall like a death rattle.

“Thus, despite your blindness, both to light and to faith, we grant you the boon of noble death.”

A scream ruptured the air. Thousand-toned. Repulsive. Ululant. Stinking with a hatred beyond death. It invaded Sawala’s bones—the tintinnabulation of a hundred bells, red-hued and obscene. He could not help but shudder, and could feel those around him share the selfsame sentiments.

The voice, however, did not falter.

“You will bring down the Goddess’s judgement down onto your people’s heads.”

They didn’t see it coming. Really, no one did. Not even its progenitors could have foretold it.

The AP fleet had made headway. Hetman So’s dreadnought, the heavy-hitter of the Huy’s left flank, had been obliterated, and orders had been issued from some Hetman to retreat to the moon’s surface in order to prepare the defense. The sally had failed.

Then, there was a flash of light. In truth, it was not much different than the thousands of others that dappled the stars with their silent bursting, though perhaps a bit more intense in its brilliance.

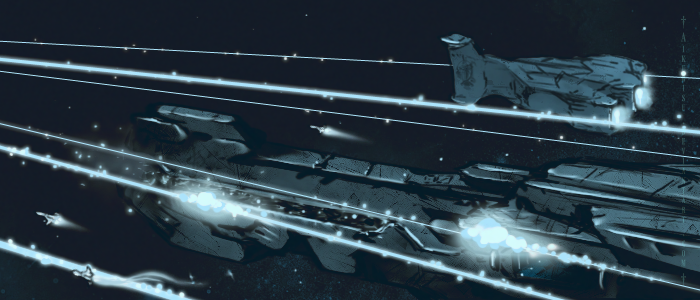

If the beast let out another scream, there was none to hear it in the void. Like an orchid, or a fulgurous growth, a sinuate appendage, bristling with grasping fingers, the

il-ship bloomed from the third cargo hold of the carrier ship

Mohingas.

It ate the nearest frigate, the

Yuenaga, along with its escort detail and a smattering of ships-of-the-line, in a single gulp. A spade of comm-pings flared and were extinguished within a breath.

Next, it pounced, a great stinging tail snapping behind it, into a cluster of skirmishing ships, sending a great number of them reeling into their formations at near-light speeds. The space above Huy was convulsed with a million plumes of roseate and gold, a million spangled stellate wreckages of titanium and steel.

The

il-ship danced, feckless, famished, its hunger unending, dazzled by the luminesce. There was a kind of ecstasy to it.

The AP fleet, in less than a standard minute, was annihilated, its leavings (those that remained) scattered to the vacuum of open space.

Few detailed records have been left us from that day, but it is speculated that over six-hundred and thirty-thousand ships had been deployed.

Yet even with such a grand table having been laid before it, the beast was not satisfied. A great hunger—maybe not so much a hunger, but a

pain—rumbled in its bowels. What else was there left to eat but the moon?

Like a fish spasming in its death throes, the

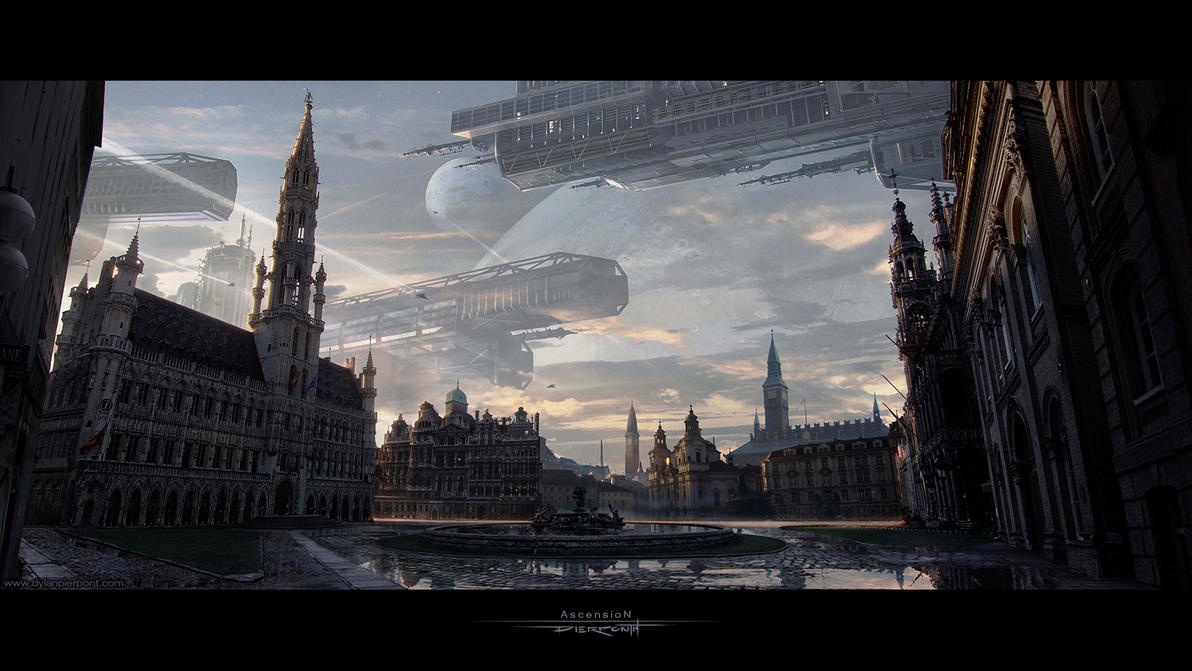

il-ship convulsed in its anguish. The lunar guard were the first to be taken—though it’s likely they didn’t know it. The moon was still asleep. It dug and dug, its maw snapping and snapping and frothing and frothing, deep into Yuhano’s atmosphere. Did any stir at their window, or part the lianas of the canopy, to see their damnation writ in the heavens?

Deep,

deep,

deep, into the core, into the pith of the apple,

down,

down,

down!

Where?

Where?

Where? All it wanted was some food to eat!

Yuhano imploded, then, cloven into three. Caught in Inur’s gravity, it was speculated that a mere seven hours remained before landfall. The spaceports were jostled, but there was little doubt. The many-armed fled in their clippers to greener pastures; the others imagined the lights in the sky as the gleaming earrings of Hanapa. The rest is already known.

The

Acquiescence, as it came to be known long days after, truly merited the name.

Year 4745 L.R., 9th Yuek

SpacePresent Day Rong-Un came to vat nine, the last of his daily patrol. The view panels were dimmed, thankfully; it was never a pleasant task to see the eyes, open perpetually, massive and hollow and dark, watching him at his inspections.

It was not as though he was afraid of the beasts. Rather to the contrary, he found them a perverse source of fascination. But even as an Eight-Limbed, and after such a time, he still thought it difficult to meet their gaze.

It was of no consequence. He went about the routine, as per usual. With a flourish, he drew up four holographic panels, a brief mote of turquoise luminescence in the cavernous chamber. With his first pair of arms, he set about monitoring the metabolic processes; with the second, he conducted a no-ray scan, in order to determine if any abnormalities were present in this specimen in particular, and to check for the presence of anti-rejection serums in the bloodstream; and with the third, a most wicked task, he exposed the dormant cerebrum to the mercurial current of the no-field.

All Rong-Un performed with circumspection and unconscious precision. He had carried out such duties for three cycles, and by now it was rote.

The only task left him was physiognomic observance. This usually consisted of merely a cursory glance, a comparison with the tri-quarterly accountings to see whether any changes had affected themselves in that period. Usually there were none—the

il-ship transformation was an elaborate and laborious project. But even so, it was not unheard of.

Hanapa teaches that not only our eyes give us recourse to brush the truth—from where, then, would faith emerge? Sometimes the things that we cannot, or have not seen are those which hold the most power over us.

Rong-Un did not muse over such teachings as he, with his fourth pair of limbs, ignited the view panels of vat nine. The great

il-ship bobbed listlessly in the zero-gravity of its chamber. It was hopelessly massive and wretched to behold, and once more, the vast ovoid eyes, starless and inky in their infinity.

As always, their gaze unsettled him for a moment, although little beyond a brief start. He busied himself with other things. The physiognomic observance was normal, and no aberrations or mutations could be caught by the naked eye.

He contemplated the creature for a moment, not really understanding why.

I wonder if it’s hungry? Rong-Un smiled briefly.

Then, he turned off the lights.